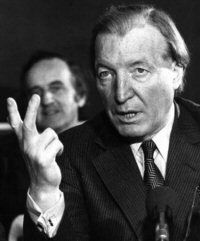

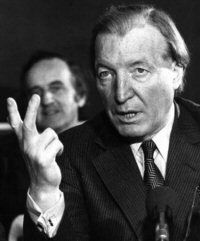

In honour of the recently published (2,400 page) Moriarty Tribunal report, I thought I'd post 20 pages from my last novel, Jude: Level 1. In these chapters, (spoiler alert!) Jude is shot at by Charles J. Haughey, "heroic leader of the Fianna Fáil Party, former Taoiseach, Celtic Chieftain of all the Gaels, gun-runner, phone-tapper, tax-dodger, cute hoor and Saviour of Ireland." He also accidentally kills Dan Bunne, "Supermarket Magnate, and one of the great Political Donors of our Age". And he ends up in a Mexican stand-off with the man who made him homeless, Jimmy "Bungle" O'Bliss, "Ireland's greatest property developer"...

In honour of the recently published (2,400 page) Moriarty Tribunal report, I thought I'd post 20 pages from my last novel, Jude: Level 1. In these chapters, (spoiler alert!) Jude is shot at by Charles J. Haughey, "heroic leader of the Fianna Fáil Party, former Taoiseach, Celtic Chieftain of all the Gaels, gun-runner, phone-tapper, tax-dodger, cute hoor and Saviour of Ireland." He also accidentally kills Dan Bunne, "Supermarket Magnate, and one of the great Political Donors of our Age". And he ends up in a Mexican stand-off with the man who made him homeless, Jimmy "Bungle" O'Bliss, "Ireland's greatest property developer"...

No similarity to any person either living or dead is intended or should be inferred. Especially to Charles J. Haughey, Ben Dunne, or, most of all

((Julian's lawyer wrenches Julian's hands off the keyboard at this point.))

CHAPTER TWENTY SIX

I determined to leave the hospital immediately, and have no more to do with women. My clothes having been destroyed, the hospital authorities issued me a pinstripe suit, from the stock of charitable clothing out of which they habitually re-clothed injured street drinkers before their discharge. The lady Doctor attempted to persuade me to stay for a week's further treatment, to stabilise my erectile nose, but I could not bear to stay another hour. When she realised there was no changing my mind, she left me, to return some minutes later with a brown paper bag.

Silently she gave me the eloquent gift of sandwiches, and left the ward without turning back.

I paused only to say good-bye to Miguel de Navarra, my Mexican neighbour. He looked up from the Galway Advertiser and shook my right hand sorrowfully with his right hand.

"This Banana," he said, waving the Illustrative Fruit with his left, "Is a weapon of Oppression."

I nodded. "Can I have it, so?" I said.

I left the hospital with only a brown paper bag full of sandwiches, a banana, and a broken heart.

During the long morphine dream of my stay in hospital, Galway had changed. Most of its buildings had been knocked and replaced with buildings one storey taller. Many of these new buildings were now, in their turn, being replaced with buildings two storeys taller again. I grew confused and lost among the taller storeys and the construction's confusions. All about me as I walked I heard talk of Shares and Options, of New Technologies, Investment Properties, and Easy Money. Galway seemed to be accelerating into the new millennium in an explosion of optimism and cement dust. Fellow teenagers passed me in Mercedes-Benz cars, often several times, trying in vain to find a place to park.

A shoe-shine boy offered me a share tip as I passed Griffins' Bakery, and the street entertainer, Johnny Massacre, was now swallowing swords of gold.

I finally found Saint Nicholas's Church, my beloved home. I was surprised to see the entire Church of Ireland population of Galway outside it, weeping and wailing in the shelter of a golf umbrella. Far above them, a fat man atop a high ladder was nailing a "SOLD" sign to the Bell Tower. The fat man turned to address the crowd. His lower face was covered by a scarf.

"Feck off,” he told them. “It's mine now.”

"Who is that masked man?" I enquired.

"'Tis Jimmy O' Bliss," sobbed the pensioner holding the umbrella.

I reeled. Jimmy “Bungle” O'Bliss was Ireland's greatest living Property Developer. No deal of his had ever fallen through. His fame had spread even to Tipperary, where he had bought the abattoir and converted it into luxury eco-friendly apartments, using only paint and plywood. This was the crack of doom for Saint Nick's.

O'Bliss descended, the better to address the pensioners.

"Ye selfish bastards! Don't ye care about Galway's homeless?" He wiped a tear from his eye with a silken 'kerchief. "All those young, unmarried management consultants, without a roof over their heads? Dear God, you people have hearts of stone."

"But 'tis our Church," quavered a pensioner.

"Pah! I bought it fair and square, at auction, for a grand."

"Auction?"

"Look, it's not my fault if somebody forgot to put a reserve on the property. Next thing you'll be telling me it's my fault that the other bidder came down with the flu and broke both his arms."

"The flu doesn't break your arms."

"This flu does."

"But where will we worship? Wed? Baptise?"

"Amn't I providing you with a Portakabin out near Menlo, for the love of God? What more can I do? Do ye want to ruin me, with your religious shenanigans? Have ye any idea what it'll cost me to replace this knackered wreck with decent townhouses, with ground-level Retail Premises? If I hadn’t got an offshore client for all these old stones, I’d hardly bother."

"But... what of my Bell Tower, my Home?" I burst out.

"Oh the Bell Tower stays."

I breathed a sigh of relief.

He nodded. "We're enhancing it into a twelve-storey, Swedish, state-of-the-art, automated vehicle-storage tower facility."

"So I can continue living there, then?" I said, in happy confusion.

Jimmy O'Bliss winked at me.

I relaxed.

"No," he said. "It's a fecking carpark, you big gom."

Having lost my Job, my Good Looks and my True Love in swift succession, I had come Home to find that I had also lost my Home. My sandwiches slipped from my fingers to land in the mud, my legs trembled and gave way, and I fell to my knees in the muck and rain...

CHAPTER TWENTY SEVEN

The National Anthem rang out in thin, high, single notes from the inside pocket of the lumpy navy jacket of Jimmy "Bungle" O'Bliss.

The National Anthem rang out in thin, high, single notes from the inside pocket of the lumpy navy jacket of Jimmy "Bungle" O'Bliss.

As I knelt, in my devastation, in a puddle, Jimmy O'Bliss high-stepped over me. Pulling a small telephone from his inside pocket, he dislodged a bulging Brown Envelope. It splashed into the puddle in front of me.

A strangely familiar voice came tinny from the tiny telephone, its tone a question.

"I got it, Big Man," replied Jimmy shortly. “Deal's done and dusted." He poked at the little machine, and slid it back into the empty inside pocket.

He stopped. Withdrew his hand. Slapped the pocket.

He stared all around, then down at the ground. With a start and a grunt, he glared at me, then scooped the soaking brown envelope from the muck and thrust it, mud and all, back into his inside pocket.

"You saw nutting," he said, and walked rapidly away.

Wet-kneed, I pulled a disconsolate sandwich from its damp brown wrapper.

My initial bite met with unexpected resistance. I could not recall a tougher crust. I removed it from my mouth to have a look at it. It was green. It had an elastic band around it. I looked at the wet brown paper bag I had taken it out of. It wasn't a bag.

A curious hush had fallen over the crowd. "'Tis the legendary Brown Envelope," whispered one ancient.

I looked back at my sandwich. It wasn't a sandwich.

I gave pursuit.

"Sir!" I cried as I ran.

He did not appear to hear me over the noise of construction. I almost caught up with him on High Street, but the demolition of Sonny Molloy’s shop sent a cloud of dust billowing.

Jimmy O’Bliss vanished.

By the time the rain had damped the dust down, he was gone.

There! At the far end of Quay Street.

But when I got there, he had crossed to the Spanish Arch, where a helicopter sat, in the lashing rain, on Buckfast Plaza. Above it was a blur of whirling blades which blew the surface water off the Plaza in a great circle about it, so that it rained sideways, as well as from above, on the young men nearby as they leaped a limestone bench on their rollerskatingboards.

It rained sideways, too, on the woman in black who fed the white Corrib swans that had gathered below her on the river.

The woman in black turned, to stare at me. I took a step towards her. The swans began to swim obliquely away, across the Corrib, towards the Claddagh Basin and its rich sewage outfalls.

Her eyes, now, were all I could see; her body, her face, her head wrapped tightly in black as she stood in the horizontal and vertical rain.

There was something unusual about her eyes…

This woman, I thought, could mean something to me. This woman of whom I know nothing, could tangle her destiny with mine. I merely have to take another step, and speak, and the threads of our destiny cross, and who knows where it will end? Together on some tropical island? In wild flight? In love? In madness?

She stared into my eyes. I shuddered with possibilities. On the blankness of her canvas I painted future after future.

In the distance, the white birds moved, slowly.

She turned, and walked away, over the bridge to the Claddagh, following them obliquely in her vertical rain.

Behind me the helicopter’s blades sped up. I turned away from her, to face my horizontal rain.

The helicopter was marked with familiar bold greens. Celtic Helicopters, I thought. The company owned by the family of the much-loved Charles J. Haughey, heroic leader of the Fianna Fáil Party, former Taoiseach, Celtic Chieftain of all the Gaels, gun-runner, phone-tapper, tax-dodger, cute hoor and Saviour of Ireland.

Jimmy O'Bliss leaped aboard, and the helicopter whined and rose immediately.

As I reached it, it was already above my head. Eager both to return the poor man's envelope with its huge wad of banknotes, and to regain my sandwiches, I bounded up onto the limestone bench, scattering the rollerskatingboarders, and leaped high, grabbing with my free hand one of the two fat rails or skis on which it had previously been resting.

I began to regret my rash impulse when the helicopter lurched, turned and began to head out across the water.

The mouth of the river opened into the sea.

The helicopter swung low above the rain-swept wave crests. My weight seemed to tug it lower by the second. My hand began to slip. With my other hand, I crammed the Brown Envelope down alongside the banana in the inside pocket of my pinstripe jacket. Then, with both hands, I hung on.

Dear God, was this the end of me?

Slowly, surely, my strength faded...

As we approached the Aran Islands I made out the black bulk of Inis Mór, then Inis Meáin, then Inis Óirr... Far below me I saw the rusting hulk of an enormous cargo vessel, hurled by storm up the beach and into the rocky fields, long before I was born.

Then we were above the sea again, and into a thick wall of offshore mist. There was no sea and no sky and I had the curious illusion that, were I to let go of the helicopter, I would simply hang where I was, suspended, cushioned on all sides by the cotton wool mist, as the helicopter laboured away from me and vanished.

Cushioned, suspended, no effort, no noise...

My weary fingers began to relax their hold. No! I fought this treacherous vision of comfort, and with numb hands hauled myself higher on the ski, and slung a leg up onto it, and managed, at length, with difficulty, one-handed, to button my jacket around the ski so that my weight was half-supported by my jacket, in which I now hung as in a sling. My aching hands could relax a little.

Then, from out of the mist, loomed the terrible and wonderful shape of the fourth Aran Island.

Hy Brasil…

Yet it did not look right. Its bleak profile should have been familiar from old photographs in the Lifestyle Supplements, back when our Chieftain still gave interviews, before disgrace and self-imposed exile. But no, the familiar dark bulk was half-eclipsed by a great white mountain thrusting out of the water, hard against the island. White fog condensed and rolled off its sides, to form an enormous ring about the white mountain.

The white peak itself, to my exhausted, wind-wracked eyes, seemed to resemble a giant Nose rising from a submerged Face. There were two dark ovals near its peak resembling nostrils . Yes, a Nose sticking up out of the waves. But this, I realised, must be a Neurotic Delusion, caused by the traumatic mutilation of my own nose. I felt delighted at my sophistication. To have acquired my very own Neurosis after so short a time in the Big City! Or, I mused, perhaps I was Hallucinating: an even more sophisticated Metropolitan response to reality, and one conferring great status back at the Orphanage. Thady Donnelly had not been right for a week after doing mushrooms on his way to the 1996 All-Ireland hurling semi-finals in Thurles, and the younger orphans had followed him around the Orphanage Grounds, beseeching him to speak of his Visions, till he finally Came Down on the following Friday…

We approached the white peak which masked the dark island. The helicopter flew low over it, and a powerful downdraft sucked us lower still, so that we staggered from the sky to within a few metres of the White Mountain. Even above the Roar of Blades and Engine, I heard Jimmy "Bungle" O'Bliss and the pilot exclaim to their Maker.

The lurching recovery of the helicopter, as it shot back up to a decent height, was good news for the occupants of the helicopter, though of slightly less benefit to me. My numb fingers had been shaken loose by the sudden fall, and all the buttons on my Charity Suit now gave way under the tug of the sudden rise.

For a moment I hung suspended, as the ski-tip caught in my inside jacket pocket... But the pocket ripped.

CHAPTER TWENTY EIGHT

I fell thrice my height, to strike the White Mountain a glancing blow with my Arse.

The entire mountain rang like a bell, with a hollow, crystal-clear chime. I skidded, bounced, skidded and began to pick up speed as the sloping shoulder of the mountain dropped away beneath me. My sliding descent through the Arctic air grew pleasing to me, and I began to control my course by movements of the shoulders and hips.

Bruised but exhilarated, I hurtled off the last ledge of the iceberg and crashed down to the shingly beach, which was knee-deep in a cushioning layer of slush and fallen ice.

I looked about me, as I brushed the slush from my pinstripe suit. The iceberg almost filled the tiny natural harbour of Hy Brasil.

I turned my back on harbour, iceberg, Aran Islands and Ireland, and walked inland.

The shingly beach became, by imperceptible degrees, stony fields. There were signs of construction work: rough stone channels cut into the unique black limestone of the island and away across the desolate fields.

I looked back, and from this slight elevation could see that the towering mountain of ice was no longer a free-floating berg, but had been pushed or hauled or driven ashore, and up the gently sloping offshore sheet of basalt which surrounded the island.

Why, he is irrigating the fourth Aran Island in the time-honoured way of the nomadic desert peoples of Arabia, I realised. He has towed an iceberg here from the poles. My respect for the genius of Charles J. Haughey grew greater still. Was this not a potent Metaphor for his benign stewardship of Ireland herself? Had he not inherited a desolate island, parched of self-belief, and remade her into an Earthly Paradise flowing with, awash with, drowning in...

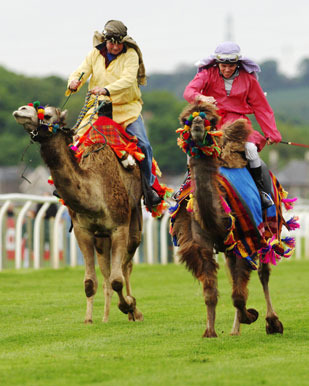

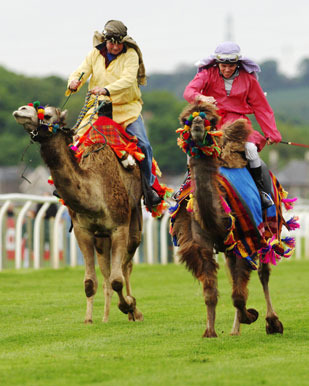

I was distracted from my Metaphor by a distant whinnying. Charles J. Haughey's famous string of racing camels! A generous gift to the then-Taoiseach from an Arabian admirer in the 1970s, all Ireland knew their fame. These beautiful beasts reputedly ran wild upon Hy Brasil. Further away again, I heard a curious cracking or crackling noise. It echoed back off the vast North Face of the towering iceberg and mingled with the whinnying, confusing my senses so that I could not make out the direction from which it came. I resolved to head further inland, for it was my vague recollection from the half-remembered Sunday colour supplements that Charles J. Haughey’s palatial retirement home was on the far side of the island from the harbour, facing only the bleak Atlantic waves, so that the great man would not have to look upon the Ireland that betrayed him.

I was distracted from my Metaphor by a distant whinnying. Charles J. Haughey's famous string of racing camels! A generous gift to the then-Taoiseach from an Arabian admirer in the 1970s, all Ireland knew their fame. These beautiful beasts reputedly ran wild upon Hy Brasil. Further away again, I heard a curious cracking or crackling noise. It echoed back off the vast North Face of the towering iceberg and mingled with the whinnying, confusing my senses so that I could not make out the direction from which it came. I resolved to head further inland, for it was my vague recollection from the half-remembered Sunday colour supplements that Charles J. Haughey’s palatial retirement home was on the far side of the island from the harbour, facing only the bleak Atlantic waves, so that the great man would not have to look upon the Ireland that betrayed him.

I headed directly across the black limestone island, featureless except for the dry stone walls around the dry stone fields and the occasional shallow labourer's grave, cut with a Kango hammer into the raw stone. Here and there, a white arm bone protruded.

The going was extremely difficult, as I scrambled down and up the steep rocky gullies in whose shelter grew ferns and mosses and orchids.

I was breathing heavily when the Salmon unexpectedly leapt in my rear pocket. I hauled it out, and received its Wisdom.

An oblique walk across an area of open crag is a continuous struggle with little cliffs and ridges and gullies, with no two successive steps on the same level, whereas if one follows the direction of the jointing, smooth flagged paths seem to unroll like carpets before one.

-Tim Robinson, English writer of Irish sympathy, Stones of Aran: Labyrinth, 1995

Walking with the grain of the landscape, I made far better time.

A thrill of delight ran through my chilled body at the thought that I might soon lay eyes upon the Great Banqueting Hall of our deposed Chief, and that I might be invited to partake in his fabled hospitality.

As I crested the windswept hill I saw, sheltering behind a tall boulder from the wind, the noble profile and imposing brow, the long, sweeping eyelashes and strong jaw, of a racing camel. It turned and gazed with its warm, liquid eyes into my eyes.

"Hullo Camel," I said to it.

It whinnied. There was a crack, another crack, and the noble beast slumped to its knees as though shot.

From the doorway of his palatial retirement mausoleum, former Taoiseach Charles J. Haughey, the smoke curling from the barrel of his rifle, trotted with dainty tread down the broad granite steps and across the gravel. He was followed by the masked figure of Jimmy O'Bliss, and by Dan Bunne, the Supermarket Magnate and one of the great Political Donors of our Age. Our greatest living Retailer, our greatest living Developer and our greatest living Politician! We would have been naked, homeless and ideologically incoherent without them. They had given us so much, no wonder they looked so Wrecked.

From the doorway of his palatial retirement mausoleum, former Taoiseach Charles J. Haughey, the smoke curling from the barrel of his rifle, trotted with dainty tread down the broad granite steps and across the gravel. He was followed by the masked figure of Jimmy O'Bliss, and by Dan Bunne, the Supermarket Magnate and one of the great Political Donors of our Age. Our greatest living Retailer, our greatest living Developer and our greatest living Politician! We would have been naked, homeless and ideologically incoherent without them. They had given us so much, no wonder they looked so Wrecked.

"Great shot, Big Man, great shot, head shot, hard shot, great shot," said Dan Bunne, his voice somewhat muffled by his constant chewing on a piece of gum.

"Shut your hole, Bunne, you fucking spastic mong," said Charles J, "You're giving me a fucking headache."

The camel, its eyes now glazed and untenanted, toppled slowly sideways. Charles walked up to the dying beast and, carefully aiming behind its ear, fired a final shot into its brain. The camel’s flanks subsided as its last breath shuddered from its throat, rattling its relaxing tongue out of the way in a staccato spray of spittle.

It was not how I had imagined meeting my hero, Charles J. Haughey, but one cannot entirely control one’s destiny. I stepped forward and reached for my inside pocket, intending to return the brown envelope full of money to its rightful owner, Jimmy O'Bliss. I cleared my throat.

The three Giants of Old Ireland failed to notice me, Dan Bunne being distracted by a lock of his own matted hair, and the others being distracted by Dan Bunne. The lock of Dan Bunne’s hair swung in the breeze, slightly to the right of his right eye. Unable to see it clearly by turning his eyes, he was turning his head.

The hair, being part of his head, turned an equal amount.

He swung around on his heel in an attempt to take the lock of hair by surprise. It remained slightly to the right of his field of vision. He began to pirouette, then reversed direction.

He fell over. Charles J. Haughey sighed.

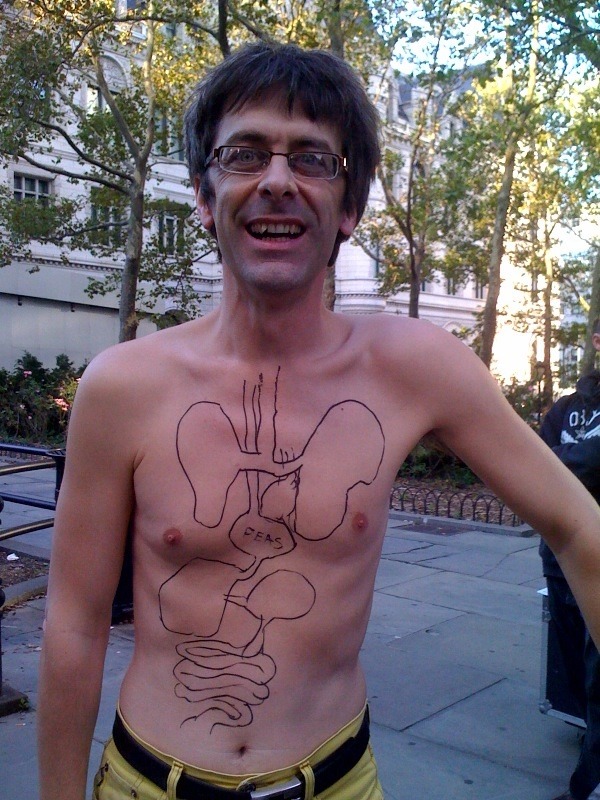

My fingers, still numb with the cold and locked in a clawlike grip from my helicopter ride, fumbled in my torn jacket pocket for the envelope and grabbed the banana instead, which had become stuck in the lining.

"Shite," I said.

Charles Haughey and Jimmy spun around and saw me for the first time. Dan looked up, blinking and chewing.

Charles Haughey stared at me with the most bloodshot eyes I had ever seen, until I looked down at Dan Bunne's. Their shirts were delightful.

I was pleased that I looked so natty in my pinstriped suit. The bulge of the stuck banana, though, was ruining the cut of my jacket. I tried to jerk it free.

“Drop the gun,” said Charles Haughey.

“Gun?” I said, bewildered, and gave another tug on my banana.

“Don’t play the innocent with me," said the former Taoiseach. "Freeze."

"I'm already frozen."

"Shut it, funnyman," said Charles J. Haughey.

"He's after the fifty grand," said Jimmy O'Bliss. "I know that fecker from earlier, at Saint Nick's. Oldest trick in the book, kneeling, trying to trip me. He must have followed me in another chopper."

"Which reminds me," said Charles Haughey. "Give me that money for safekeeping while I think what to do with our Mafia chum here."

I began to realise that they had grasped entirely the wrong end of the metaphorical stick.

Jimmy reached into his pocket and brought out a sodden brown paper package. "It fell in a puddle boss, sorry," he said.

Charles J. Haughey grunted and, without taking his eyes off me, ripped open the brown paper with his teeth.

He glanced down at what he held.

"What. The fuck. Is this."

He looked upon my cold toast and chocolate spread sandwiches with a wild surmise. He looked up at me, then across at Jimmy. His eyes grew more bloodshot on the instant, as though a small blood vessel had burst.

"My God. He takes my money and he comes back for more." He looked me up and down with an expression that bore a most curious resemblance to respect.

"I can explain," I said.

"Or die trying.”

"I have your money here in my pocket. I merely wish to return it..."

"Bollocks. You have a gun in that pocket."

"No, that is a banana."

"Who are you trying to cod? It's a gun."

"A banana"

"Gun"

"Banana"

"Gun"

"Banana"

Dan Bunne had meanwhile stood up, and now chose this moment to spin anti-clockwise upon his left heel, in an attempt to sneak up on his lock of hair from the far side.

He failed. He fell over. His gun went off.

I jerked in reaction, and the banana flew out of my pocket, as Dan Bunne said, "Sweet Jesus Big Man, I've shot myself in the foot!"

Jimmy O’Bliss fell over.

“Oh no, wrong, cancel that, I’ve shot Jimmy in the foot,” said Dan Bunne, and tried to spit out his chewing gum. Nothing emerged but a small quantity of pink spit. "Dear God! I have been chewing my own cheek this past hour!" exclaimed Bunne. “Isn't that gas, now? Hah? Hah? Hah?" He spat more pink spit and had a poke at the inside of his mouth with a jittery finger.

Charles J. ignored him and the yelping Jimmy. "Well, you were telling the truth about that banana. So give me my money."

I delved deeper into my pocket to retrieve the fifty thousand pounds. My fingers slid down, and along the bottom seam, and up the side seam, and out the gaping flap of the ripped, empty pocket.

"You'll never believe what I'm going to tell you," I said to Charles J. Haughey.

Charles took a step towards me, raising his gun, a semi-automatic weapon that appeared custom built. Dan Bunne’s long barrelled goose-gun had a magazine big enough to contain a full box of cartridges. Jimmy O'Bliss had just dropped a Browning large-calibre sniper rifle.

"Are such weapons not illegal in the Republic?" I enquired, interested.

"We're not in the Republic now, Pinocchio,” said the former Taoiseach, stroking his trigger and stepping closer. “This island is extra-territorial. It's beyond the remit of the glorious fucking Republic."

"Which is handy if you're bringing in workers, and you don’t fancy the paperwork…" said Dan Bunne cryptically, with a wink.

"Shut the fuck up, Bunne," said Charles J. Haughey, scowling. He turned back to me. "I am the law here. I am Judge, Jury and fucking Executioner."

A vivid metaphor indeed, I thought. He had not lost his oratorical panache.

“Hang on here a minute,” I said.

I picked up my banana, and ran.

CHAPTER TWENTY NINE

Obviously, the pocket had ripped open after being snagged on my fall from the helicopter. The great wad of cash could have slipped out at any point since. My only hope of clearing up this misunderstanding lay in recovering the money from where it had fallen and returning it, as proof of my bona fides. No doubt we would soon be laughing about their ludicrous mistake over a pewter goblet of hot mead. I retraced my route as exactly as possible, hopping into the fern-filled high-walled channels in the limestone and running along them for a while before leaping out and tacking across the grain of the land, leaping the channels at right angles, before dropping back into another for a long, oblique run.

Further and further behind me followed Charles and Dan.

I made it back to the beach with little incident, but there was no sign of the envelope. I clambered from the beach to the iceberg across a shifting mass of collapsed, melting debris.

Cracks and fissures provided hand- and foot-holds in the hard, frictionless surface, and with difficulty, often on all fours, I retraced the path of my easy descent. The ice creaked and cracked beneath me, whole slabs sometimes peeling away as I searched for a solid handhold.

At one point, spread-eagled on the face of a flat cliff of ice, I noticed a curious phenomenon: the ice exploded out in a small spray of shattered fragments just a foot to the left of my head. When I leaned across to look at the strange hole or crater revealed, the same phenomenon took place a foot to the right of my head. I looked back at Charles and Dan to see if they could explain this curiosity, but they seemed busy, a little way up from the base of the iceberg, fiddling with their guns. Not wishing to distract them, I pulled myself up over the lip of the cliff and kept climbing, hidden from them now by the high flank of the berg.

At last, I reached the top:

And there it was, pristine upon the peak: the Brown Envelope, lying where it, and I, had first fallen.

I relaxed and awaited the others’ arrival. It had been an exhausting climb, and I was glad of the chance to rest and eat my banana. Though bruised from the morning's events, its flesh was sweet ambrosia to me. I warmed myself with the thought of how relieved and delighted they would be to have their money returned to them.

I relaxed and awaited the others’ arrival. It had been an exhausting climb, and I was glad of the chance to rest and eat my banana. Though bruised from the morning's events, its flesh was sweet ambrosia to me. I warmed myself with the thought of how relieved and delighted they would be to have their money returned to them.

They seemed a long time coming. Dan Bunne had no doubt been slowed by his unsuitable shoes.

At length I heard their slow, almost cautious approach. "Up here!" I cried. "Come and get it!"

The boom and echo of my voice shook free several ledges of snow, and, disintegrating, they were whirled away down the berg by the chill wind. A split in the ice at my feet widened. I dropped my banana skin into it. The splayed yellow star vanished, tumbling, into the darkness.

A low creak came from the depths.

Charles Haughey’s rifle barrel appeared over the ridge, wearing a hat. I laughed at his prank. "Come up here and I'll give it to you!" I shouted, anxious to put the whole embarrassing misunderstanding behind me.

From behind me, I heard the crunch of footsteps on fresh ice crystals. I turned in time to see Dan Bunne appear from over the far side of the frozen peak. He was looking at his feet, stepping carefully around the rim of the enormous nose-holes.

“I’ll give it to you right now. You asked for it,” I said, reaching for my pocket, “And now you’re going to get it.”

Dan Bunne swung the long barrel of his goose-gun in my general direction and convulsively pulled the trigger. The massive recoil sent him skidding a full three yards backwards on the smooth leather soles of his Italian shoes. This would not have been so bad had he not been standing two yards from the edge of the Northernmost Hole.

I reached the edge too late to save him. "Dear God!" he cried as he fell. "The Snorter has become the Snorted! It is a judgement on me!"

His hands still gripped the gun, and as he fell he fired, the recoils tumbling him end over end faster and faster till he vanished into the darkness spinning like a Catherine Wheel and emitting great blazing gouts of burning cordite with each report of his weapon until he had exhausted its capacity.

The explosions echoed and re-echoed long after the last blast of flaming gunpowder had scorched the Arctic air. A booming rumble began as the last echoes died, and grew louder. Ice cracked and split far below.

I stepped back from the edge of the Hole as the edge crumbled and fell in. A hairline fracture appeared in the hard ice beneath me. It ran past me in both directions, to the cliff edges.

It widened to an inch, two inches...

The left side of the peak suddenly fell a full foot.

I had a remarkably bad feeling about this.

With awful slowness, the iceberg began to split down the middle.

CHAPTER THIRTY

As the shuddering iceberg began to split, I tried to decide which side of the divide would be the better one to ride out the collapse upon. Yet the great noise made thinking difficult.

As the shuddering iceberg began to split, I tried to decide which side of the divide would be the better one to ride out the collapse upon. Yet the great noise made thinking difficult.

My mind was finally made up by the arrival over the ridge of Charles J. Haughey. Perhaps in some way blaming me for the destruction of his iceberg and the death of his oldest friend, he loosed a wild shot at me from close range. I prudently leaped the widening chasm, and found myself falling inland atop a cliff of ice, as Charles J. Haughey’s side of the iceberg fell away from me, out to sea.

I wedged myself in a fissure, and endured the accelerating fall.

My half of the split mountain toppled inland, its broad point of contact rolling up the shingly beach and across the stony fields, ever faster, until the very peak slapped against the stony hill crest and snapped off, countless tons of ice now tobogganing down the far slope to overrun the retirement home of Our Great Leader, coming to a halt now in its ruins.

I emerged from my fissure, and slid and fell down off the ice, through the shattered roof, and into the Imperial Bedroom.

I landed upon the plumped, heaped, purple satin pillows.

Sitting at the foot of the bed, bathing his wounded foot, happily untouched by the falling lumber, masonry, and ice, was Jimmy O'Bliss. He looked back at me over his shoulder with an expression I found difficult to interpret, due to the scarf obscuring his lower face.

He stood, and hopped at high speed from the room.

CHAPTER THIRTY ONE

I was delighted by this unexpected chance to return to Jimmy O' Bliss his packet of money. Still shivering from the icy peak, I wrapped myself in a beautifully soft sheet of rich Egyptian cotton, and pursued him down the main stairs, through the banqueting hall, into the kitchens, down into the cellars, and further down into the sub-cellars and past a dark tunnel-mouth.

Then back up again.

Finally, as loss of blood slowed the modest and reluctant old fellow, I cornered him in the banqueting hall. Above us, the clear glass roof was spangled with chunks of ice, and, above that, the shuddering overhang of the iceberg itself was a rich, dark blue you could almost mistake for an evening sky, were it not for the facthe

that it dripped and creaked. Out through the French windows I could see the open-air swimming pool. A camel swam in its limpid waters. I advanced towards Jimmy and pressed the banknotes into his trembling hands. "You dropped this," I said, and turned to go.

"Wait," said Jimmy in a weak voice, and I stopped, and turned. "One moment... I know it's here somewhere..." He opened a wooden cabinet and rooted around in its interior. Was I finally to be offered a glass of mead, in thanks for my kind deed? Jimmy O'Bliss emerged with a bolt-action rifle.

"You're too fucking dangerous to live, Sonny Jim," he said, cocking the gun with a snap of the bolt. A tremor ran through the cliff of ice overhanging us, rattling the glass roof in its frame. A little avalanche of slush and melt-water ran across the glass, rippling the blue light that filtered through to us so that we seemed to move underwater. "It is a thing I never understood, in the James Bond fillums," said Jimmy O'Bliss, "why it is they always explain their nefarious plans to James Bond, and then leave him to be killed by some complicated, untried, and unsupervised stratagem. Lasers, indeed. Volcanoes. Fecking alligators… Myself and Charlie would always be roaring at the telly, 'Shoot him in the head! Just shoot him in the head!'" He sighed, pointed the gun at my head and pulled the trigger. The loud click of the firing pin on the empty chamber caused the cliff of ice above us to rumble, and lurch forward some inches. "Feck. No bullets. Hang on." He found a box of bullets in the cabinet.

"You are planning to shoot me in the head?" I said, somewhat taken aback.

"I am," he said, sliding out the empty magazine and loading it swiftly with bullets.

"That thought is a source of sorrow to me," I said, "for I am on a quest to win the heart of my true love, the most beautiful woman in Ireland and possibly the world."

"You intrigue me strangely," said Jimmy O'Bliss, pausing. "Tell me more."

I told him more.

"Sounds great. Where does she work?"

"In SuperMacs of Eyre Square."

He nodded, and closed his eyes, and smiled. “Ah, young love.” He opened his eyes. “God, I haven't ridden the hole off a young one in a long while. Yes, I have neglected the needs of the Heart.” He slammed the full magazine up into the gut of the gun with the palm of his hand. The tremendous blue ice-cliff overhanging us swayed and dropped a foot at the report. "Ah,” he sighed, “youth is wasted on the young." He swung up the barrel.

"I was intrigued by the tunnel mouth," I said.

"What?" said Jimmy.

"Mr Bunne said something, too, about workers..."

"Oh, Big Mouth Strikes Again," said Jimmy. He put aside his rifle. "Sure, I suppose it won’t do any harm… This is where the Blacks are brought in. Hy Brasil is, by a curiosity of the law, in extra-territorial waters. Then down the tunnels with them, and Barney writes the cheque....”

I was puzzled. “Is such importation of shackled humanity strictly legal?"

“Our once and future King can do whatever he fucking wants here, sonny boy. It's his rocky kingdom, the barren field of his exile. From this stony grey soil he shall gather his strength, till the people repent their treachery and call for him..." Jimmy sighed. “He dragged this shit-hole out of the middle ages and into the twentieth fucking century, and how did the people thank him? They shafted him.” He brooded a bit on this, and clarified. “They fucked him up the arse and hung him out to dry. But why am I still yapping? Old age..." He snapped up the bolt on the rifle, hauled it back, baring the chamber into which popped up, spring-loaded, a large bullet. He then slammed forward the bolt, knocking the bullet into position.

The cliff of ice above and behind him shifted, shifted again, lurched, and fell in its entirety on the banqueting hall, driving its stout pillars down through the next two floors, collapsing its own great wooden floor, the ancient carpet ripping free and sliding down the hole, so that I fell through the cellar, into the sub-cellar and rolled down the mouth of the tunnel wrapped in sheet and carpet. Jimmy, his suit snagging on a splintered joist as he fell through the cellar, did not follow me down. His rifle, jerked from his hands by his sudden arrest, did.

Now I had a gun. Jimmy did not. My position had improved.

Unfortunately, the collapsing iceberg had also breached the side wall of the open-air swimming pool, in which a camel still swam, alongside the banqueting hall.

It would have gone easier with me if the swimming pool had not been connected by a deep channel to the sea, to ensure the freshness of the bathing water: but it was: and the tide, too, being high, all the broad Atlantic attempted to follow me, camel and all, into the cellar, the sub-cellar, and, subsequently, the Tunnel.

Jude: Level 1((There you go... This episode is taken from Jude: Level 1, which will be reprinted later this year as Jude in Ireland. Jude's adventures will continue in the new novel, Jude in London, due out this September from Old Street Publishing.))

Jude: Level 1((There you go... This episode is taken from Jude: Level 1, which will be reprinted later this year as Jude in Ireland. Jude's adventures will continue in the new novel, Jude in London, due out this September from Old Street Publishing.))