Here you go. "The Orphan and the Mob": A free, award-winning, and slightly rude story, to celebrate “The iHole” making the shortlist of the BBC International Short Story Award

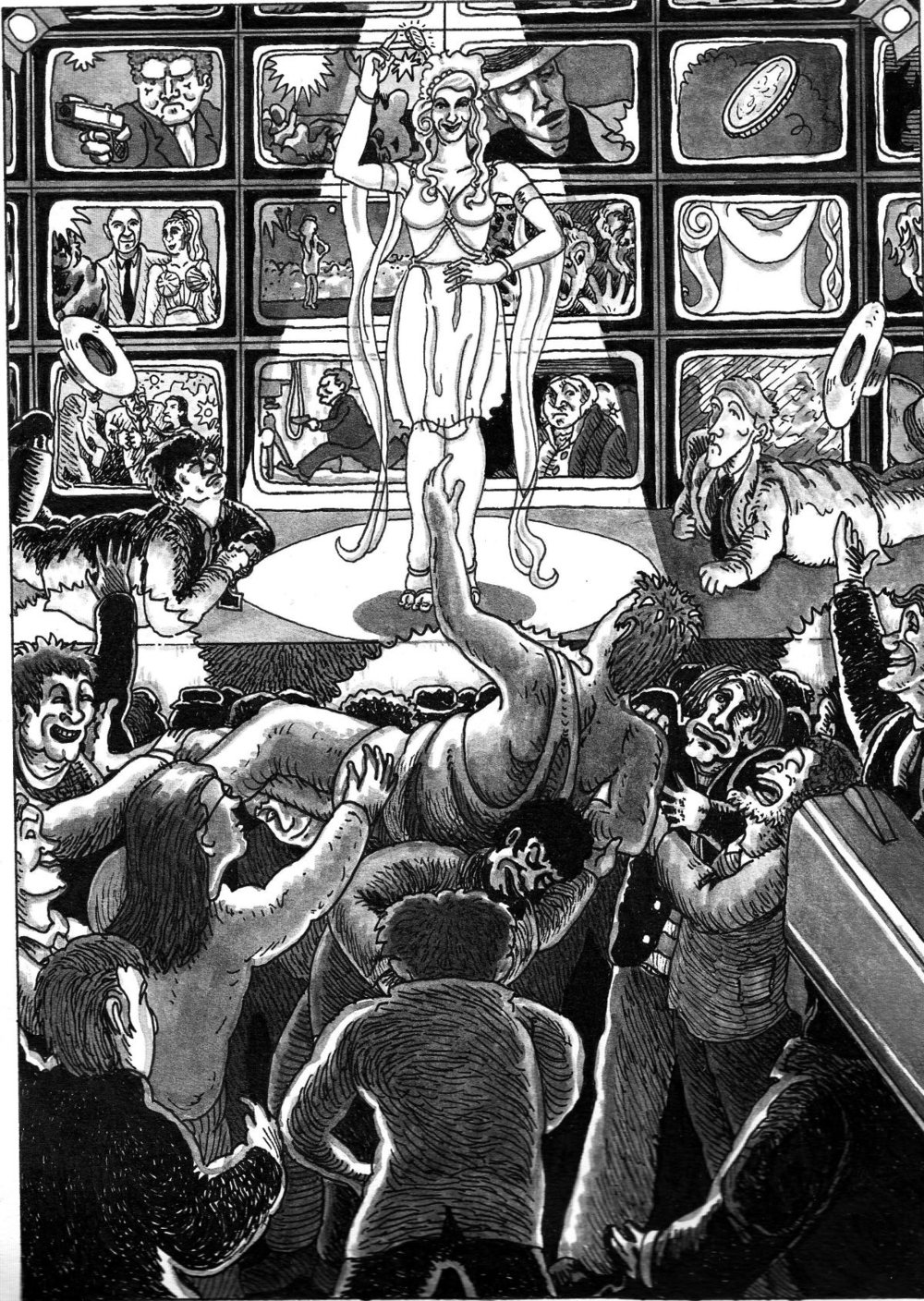

/ Gareth Allen's fine drawing (from Jude in London) of a totally different and entirely fictional prize ceremony, at which Jude is borne aloft

Gareth Allen's fine drawing (from Jude in London) of a totally different and entirely fictional prize ceremony, at which Jude is borne aloft

Woo-hoo! as Blur so eloquently put it.

My story, "The iHole", has been shortlisted for this year’s super-special, one-off, BBC International Short Story Award. (This is the literary equivalent of qualifying for the 100 meters final at the Olympics. Only with fifteen grand for the winner instead of a gold medal. And you don’t have to run, thank God.)

The ten shortlisted stories, by such splendid writers as Deborah Levy, Lucy Caldwell, and MJ Hyland, are being broadcast on BBC Radio 4, and are (or will be) also available for two weeks as free podcasts from here, and published in this book here.

So, to celebrate all that, I'm giving away my best short story that ISN'T "The iHole".

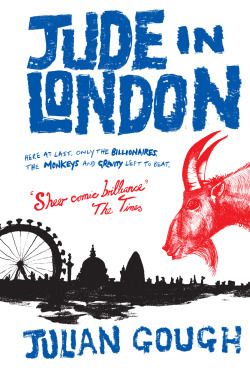

“The Orphan and the Mob” is a serious comedy, about an orphan who desperately needs to go to the toilet. (It’s also an allegory of 20th century Irish history, a visual pun on The Wizard of Oz, and quite a few other things, but shush, let’s not frighten the children.) It won the BBC National Short Story Prize in 2007 (at that time, the largest prize in the world for a single short story), and was broadcast twice on BBC Radio 4. It represented Ireland in the Dalkey Archive anthology, Best European Fiction 2010. It also forms the prologue to the novel Jude in Ireland (which the Sunday Tribune chose, in 2010, as their Irish Novel of the Decade).

OK, enough of that; you can lash into it online below. If you like it, please do tell me in the comments. And if you REALLY like it, buy the Jude novels and find out what happens next. (My long-suffering publisher, Ben, has, at my request, set the e-book prices particularly low, to entice and seduce you.)

Any questions? Ask them in the comments below, or mail me here. In fact mail me anyhow, say hello, and I’ll tell you what I’m up to, and send you the odd free story and poem.

Enjoy...

-Julian

The Orphan and the Mob

-Julian Gough

If I had urinated immediately after breakfast, the Mob would never have burnt down the Orphanage. But, as I left the dining hall to relieve myself, the letterbox clattered. I turned in the long corridor. A single white envelope lay on the doormat.

I hesitated, and heard through the door the muffled roar of a motorcycle starting. With a crunching turn on the gravel drive and a splatter of pebbles against the door, it was gone.

Odd, I thought, for the postman has a bicycle. I walked to the large oak door, picked up the envelope, and gazed upon it.

Jude

The Orphanage

Tipperary

Ireland

For me! On this day, of all significant days! I sniffed both sides of the smooth white envelope, in the hope of detecting a woman's perfume, or a man's cologne. It smelt, faintly, of itself.

I pondered. I was unaccustomed to letters, never having received one before, and I did not wish to use this one up in the One Go. As I stood in silent thought, I could feel the Orphanage Coffee burning relentlessly through my small dark passages. Should I open the letter before, or after, urinating? It was a dilemma. I wished to open it immediately. But a full bladder distorts judgement, and is a great obstacle to understanding. Yet could I do justice to my very dilemma, with a full bladder?

As I pondered, both dilemma and letter were removed from my hands by the Master of Orphans, Brother Madrigal.

"You've no time for that now, boy," he said. "Organise the Honour Guard and get them out to the site. You may open your letter this evening, in my presence, after the Visit." He gazed at my letter with its handsome handwriting, and thrust it up the sleeve of his cassock.

I sighed, and went to find the Orphans of the Honour Guard.

…

I found most of the young Orphans hiding under Brother Thomond in the darkness of the hay barn.

"Excuse me, Sir," I said, lifting his skirts and ushering out the protesting infants.

"He is Asleep," said a young Orphan, and indeed, as I looked closer, I saw Brother Thomond was at a slight tilt. Supported from behind by a pillar of the hay barn, he was maintained erect only by the stiffness of his ancient joints. Golden straws protruded from the neck and sleeves of his long black cassock, and emerged at all angles from his wild white hair.

"He said he wished to speak to you, Jude," said another Orphan. I hesitated. We were already late. I decided not to wake him, for Brother Thomond, once he had Stopped, took a great deal of time to warm up and get rightly going again.

"Where is Agamemnon?" I asked.

The smallest Orphan removed one thumb from his mouth and jerked it upward, to the loft.

"Agamemnon!" I called softly.

Old Agamemnon, my dearest companion and the Orphanage Pet, emerged slowly from the shadows of the loft and stepped, with a tread remarkably dainty for a dog of such enormous size, down the wooden ladder to the ground. He shook his great ruff of yellow hair and yawned at me loudly.

"Walkies," I said, and he stepped to my side. We exited the hay barn into the golden light of a perfect Tipperary summer's day.

I lined up the Honour Guard and counted them by the front door, in the shadow of the South Tower of the Orphanage. Its yellow brick façade glowed in the morning sun.

We set out.

…

From the gates of the Orphanage to the site of the speeches was several strong miles.

We passed through Town, and out the other side. The smaller Orphans began to wail, afraid they would see Black People, or be savaged by Beasts. Agamemnon stuck closely to my rear. We walked until we ran out of road. Then we followed a track, till we ran out of track.

We hopped over a fence, crossed a field, waded a dyke, cut through a ditch, traversed scrub land, forded a river and entered Nobber Nolan's bog. Spang plumb in the middle of Nobber Nolan's Bog, and therefore spang plumb in the middle of Tipperary, and thus Ireland, was the Nation's most famous Boghole, famed in song and story, in History book and Ballad sheet: the most desolate place in Ireland, and the last place God created.

I had never seen the famous boghole, for Nobber Nolan had, until his recent death and his bequest of the Bog to the State, guarded it fiercely from locals and tourists alike. Many's the American was winged with birdshot over the years, attempting to make pilgrimage here. I looked about me for the Hole, but it was hid from my view by an enormous Car-Park, a concrete Interpretive Centre of imposing dimensions, and a tall, broad, wooden stage, or platform, bearing Politicians. Beyond Car-Park and Interpretive Centre, an eight-lane motorway of almost excessive straightness stretched clean to the Horizon, in the direction of Dublin.

Facing the stage stood fifty thousand farmers.

We made our way through the farmers to the stage. They parted politely, many raising their hats, and seemed in high good humour. "'Tis better than the Radio Head concert at Punchestown," said a sophisticated farmer from Cloughjordan, pulling on a shop-bought cigarette.

Once onstage, I counted the smaller Orphans. We had lost only the one, which was good going over such a quantity of rough ground. I reported our arrival to Teddy “Noddy” Nolan, the Fianna Fáil TD for Tipperary Central, and a direct descendent of Neddy "Nobber" Nolan. Nodding vigorously, he waved us to our places, high at the back of the sloping stage. The Guard of Honour lined up in front of an enormous green cloth backdrop and stood to attention, flanked by groups of seated dignitaries. I myself sat where I could unobtrusively supervise, in a vacant seat at the end of a row. When the last of the stragglers had arrived in the crowd below us, Teddy cleared his throat. The crowd fell silent, as though shot. He began his speech.

"It was in this place..." he said, with a generous gesture which incorporated much of Tipperary, "... that Eamonn DeValera..."

Everybody removed their hats.

"... hid heroically from the Entire British Army..."

Everybody scowled and put their hats back on.

"... during the War of Independence. It was in this very boghole that Eamonn DeValera..."

Everybody removed their hats again.

"...had his Vision: A Vision of Irish Maidens dancing barefoot at the crossroads, and of Irish Manhood dying heroically while refusing to the last breath to buy English shoes..."

At the word English the crowd put their hats back on, though some took them off again when it turned out only to be Shoes. Others glared at them. They put the hats back on again.

"We in Tipperary have fought long and hard to get the Government to make Brussels pay for this fine Interpretive Centre and its fine Car-Park, and in Brünhilde DeValera we found the ideal Minister to fight our corner. It is therefore with great pleasure, with great pride, that I invite the great grand-daughter of Eamonn DeValera's cousin... the Minister for Beef, Culture and the Islands... Brünhilde DeValera... to officially reopen... Dev's Hole!"

The crowd roared and waved their hats in the air, though long experience ensured they kept a firm grip on the peak, for as all the hats were of the same design and entirely indistinguishable, the One from the Other, it was common practice at a Fianna Fáil hat-flinging rally for the less scrupulous farmers to loft an Old Hat, yet pick up a New.

Brünhilde DeValera took the microphone, tapped it, and cleared her throat.

"Spit on me, Brünhilde!" cried an excitable farmer down the front. The crowd surged forward, toppling and trampling the feeble-legged and bock-kneed, in expectation of Fiery Rhetoric. She began.

"Although it is European Money which has paid for this fine Interpretive Centre… Although it is European Money which has paid for this fine new eight-lane Motorway from Dublin and this Car Park, that has Tarmacadamed Toomevara in its Entirety… Although it is European Money which has paid for everything built West of Grafton Street in my Lifetime… And although we are grateful to Europe for its Largesse..."

She paused to draw a great Breath. The crowd were growing restless, not having a Bull's Notion where she was going with all this, and distressed by the use of a foreign word.

"It is not for this I brought my Hat," said the Dignitary next to me, and spat on the foot of the Dignitary beside him.

"Nonetheless," said Brünhilde DeValera, "Grateful as we are to the Europeans...

...we should never forget...

...that...

...they..."

Fifty thousand right hands began to drift, with a wonderful easy slowness, up towards the brims of fifty thousand Hats in anticipation of a Climax.

"...are a shower of Foreign Bastards who would Murder us in our Beds given Half a Chance!"

A great cheer went up from the massive crowd and the air was filled with Hats till they hid the face of the sun and we cheered in an eerie half-light.

The minister paused for some minutes while everybody recovered their own Hat and returned it to their own Head.

"Those foreign bastards in Brussels think they can buy us with their money! They are Wrong! Wrong! Wrong! You cannot buy an Irishman's Heart, an Irishman's Soul, an Irishman's Loyalty! Remember '98!"

There was a hesitation in the crowd, as the younger farmers tried to recall if we had won the Eurovision Song Contest in 1998.

"1798!" Brünhilde clarified.

A great cheer went up as we recalled the gallant failed rebellion of 1798. "Was It For This That Wolfe Tone Died?" came a wisp of song from the back of the crowd.

"Remember 1803!"

We applauded Emmet's great failed rebellion of 1803. A quavering chorus came from the oldest farmers at the rear of the great crowd: “Bold Robert Emmet, the darling of Ireland… "

"Remember 1916!"

Grown men wept as they recalled the great failed rebellion of 1916, and so many contradictory songs were started that none got rightly going.

There was a pause.

All held their breath.

"…Remember 1988!"

Pride so great it felt like anguish filled our hearts as we recalled the year Ireland finally threw off her shackles and stood proud among the community of nations, with our heroic victory over England in the first match in Group Two of the Group Stage of the European Football Championship Finals. A brief chant went up from the Young Farmers in the Mosh Pit: "Who put the ball in the England net?"

Older farmers, further back, added bass to the reply of "Houghton! Houghton!"

I shifted uncomfortably in my seat.

"My great grand-father's cousin did not Fight and Die in bed of old age so that foreign monkey-men could swing from our trees and rape our women! He did not walk out of the Daíl, start a Civil War and kill Michael Collins so a bunch of dirty foreign bastards could..."

I missed a number of Fiery Words, as excited farmers began to leap up and down roaring at the front, the younger and more nimble mounting each other’s shoulders, then throwing themselves forward to surf toward the stage on a sea of hands, holding their Hats on as they went.

"Never forget,” roared Brünhilde DeValera, “that a Vision of Ireland came out of Dev's Hole!"

"Dev's Hole! Dev's Hole! Dev's Hole!" roared the crowd.

By my side, Agamemnon began to howl, and tried to dig a hole in the stage with his long claws.

Neglecting to empty my bladder after breakfast had been an error the awful significance of which I only now began to grasp. A good Fianna Fáil Ministerial speech to a loyal audience in the heart of a Tipperary bog could go on for up to five hours. I pondered my situation. My only choice seemed to be as to precisely how I would disgrace myself in front of thousands. To rise and walk off the stage during a speech by a semi-descendent of DeValera would be tantamount to treason, and would earn me a series of beatings on my way to the portable toilets. The alternative was to relieve myself into my breeches where I sat.

My waist-band creaked under the terrible pressure.

With the gravest reluctance, I willed the loosening of my urethral sphincter.

…

Nothing happened. My subsequent efforts, over the next few minutes, to void my bladder, resulted only in the vigorous exercising of my superficial abdominal muscles. At length, I realised that there was a fundamental setting in my Subconscious, and it was set firmly against public voidance. To this adamant subconscious setting, my conscious mind had no access.

Meanwhile, the pressure grew intolerable as the Orphanage Coffee continued to bore through my system.

I grew desperate. Yet, within the line of sight of fifty thousand farmers, I could not unleash the torrent.

Then, inspiration. The Velvet Curtain! All I needed was an instant's distraction, and I could step behind the billowing green backdrop beside me, and vanish. There would, no doubt, be an exit off the back of the stage, through which I could pass to relieve myself, before returning, unobserved, to my place.

A magnificent gust of Nationalist Rhetoric lifted every hat again aloft and, in the moment of eclipse, I stood, took one step sideways, and vanished behind the Curtain.

…

I shuffled along, my face to the Emerald Curtain, my rear to the back wall of the stage, until the wall ceased. I turned, and beheld, to my astonished delight, the solution to all my problems.

Hidden from stage and crowd by the vast Curtain was a magnificent circular long-drop toilet of the type employed in the Orphanage. But where we sat around a splintered circle of rough wooden plank, our buttocks overhanging a fetid pit, here was elegant splendour: a great golden rail encircled a pit of surpassing beauty. Mossy walls ran down to a limpid pool into which a lone frog gently ‘plashed.

Installed, no doubt, for the private convenience of the Minister, should she be caught short during the long hours of her speech, it was the most beautiful sight I had yet seen in this world. It seemed nearly a shame to urinate into so perfect a pastoral picture, and it was almost with reluctance that I unbuttoned my breeches and allowed my manhood its release.

I aimed my member so as to inconvenience the Frog as little as possible. At last my Conscious made connection with my Unconscious; the Setting was Reset; Mind and Body were as One; Will became Action: I was Unified. In that transcendent moment all my senses were polished to perfection.

I could smell the sweet pollen of the Heather and the Whitethorn, and the mingled Colognes of a thousand Bachelor Farmers.

I could taste the lingering, bitter grounds of the Orphanage Coffee, and feel the grit of them lodged in the joins of my teeth.

I could hear the murmur and sigh of the crowd like an ocean at my back, and Brünhilde DeValera's mighty voice bounding from rhetorical Peak to rhetorical Peak, ever higher.

And as this moment of Perfection began its slow decay into the past, and as the delicious frozen moment of Anticipation deliquesced into Attainment and the pent-up waters leaped forth, far forward, and fell in their glorious swoon, Brünhilde DeValera's voice rang out as from Olympus

"I

hereby

officially

reopen...

Dev's Hole!"

A suspicion dreadful beyond words began to dawn on me. I attempted to Arrest the Flow, but I may as well have attempted to block by effort of will the course of the mighty Amazon River.

Thus the Great Curtain parted, to reveal me Urinating into Dev's Hole: into the very Source of the Sacred Spring of Irish Nationalism: the Headwater, the Holy Well, the Font of our Nation.

…

I feel, looking back, that it would not have gone so badly against me, had I not turned at Brünhilde De Valera's shriek and hosed her with urine.

…

They pursued me across rough ground for some considerable time.

…

Agamemnon held my pursuers at the Gap in the Wall, as I crossed the grounds and gained the House. He had not had such vigorous exercise since running away from Fossetts' Circus and hiding in our hay barn a decade before, as a pup.

Now, undaunted, he slumped in the gap, panting at them.

Slamming the Orphanage Door behind me, I came upon old Brother Thomond in the Long Corridor, beating a Small Orphan in a desultory manner.

"Ah, Jude," said Brother Thomond, on seeing me. The brown leather of his face creaked as he smiled, revealing the perfect, white teeth of Brother Jasper.

"A little lower, Sir, if you please," piped the Small Orphan, and Brother Thomond obliged. The weakness of Brother Thomond's brittle limbs made his beatings popular with the Lads, as a rest and a relief from those of the more supple and youthful Brothers.

"Yes, Jude..." he began again, "I had something I wanted to... yes... to... yes..." He nodded his head, and was distracted by straw falling past his eyes, from his tangled hair.

I moved from foot to foot, uncomfortably aware of the shouts of the approaching Mob. Agamemnon, by his roars, was now retreating heroically ahead of them as they crossed the grounds toward the front door.

"'Tis the Orphanage!" I heard one cry.

"'Tis full of Orphans!" cried another.

"From Orphania!" cried a third.

"As we suspected!" called a fourth. "He is a Foreigner!"

I had a bad feeling about this. The voices were closer. There was the thud of Agamemnon's retreating buttocks against the door. Agamemnon stood firm at the steps, but no dog, however brave, can hold off a Mob forever.

"Yes!" said Brother Thomond, and fixed me with a glare. "Very good." He fell asleep briefly, one arm aloft above the Small Orphan.

The mob continued to discuss me on the far side of the door.

"You're thinking of Romania, and of the Romanian orphans. You're confusing the two," said a level head, to my relief. I made to tiptoe past Brother Thomond and the Small Orphan.

"Romanian, by God!"

"He is Romanian?"

"That man said so."

"I did not..."

"A Gypsy Bastard!"

"Kill the Gypsy Bastard!"

The Voice of Reason was lost in the hubbub, and a rock came in through the stained-glass window above the front door. It put a Hole in Jesus and it hit Brother Thomond in the back of the neck.

Brother Thomond awoke.

"Dismissed," he said to the Small Orphan sternly.

"Oh but Sir you hadn't finished!"

"No backchat from you, young fellow, or I shan't beat you for a week."

The Small Orphan scampered away into the darkness of the Long Corridor. Brother Thomond sighed deeply, and rubbed his neck.

"Jude, today is your eighteenth birthday, is it not?"

I nodded.

Brother Thomond sighed again. "I have carried a secret this long time, regarding your Birth. I feel it is only right to tell you now..."

He fell briefly asleep.

The cries of the Mob grew as they assembled, eager to enter, and destroy me. The yelps and whimpers of brave Agamemnon were growing fainter. I had but little time. I poked Brother Thomond in the Clavicle with a Finger. He started awake. “What? WHAT? WHAT?”

Though to rush Brother Thomond was usually counter-productive, circumstances dictated that I try. I shouted, the better to penetrate both the Yellow Wax and the Fog of Years.

"You were about to tell me the Secret of my Birth, Sir."

"Ah yes. The secret..." He hesitated. "The secret of your birth... The secret I have held these many years... which was told to me by... by one of the... by Brother Feeny... who was one of the Cloughjordan Feenys... His mother was a Thornton..."

"If you could Speed It Up, Sir," I suggested, as the Mob forced open the window-catch above us. Brother Thomond obliged.

"The Secret of Your Birth..."

Outside, with a last choking yelp, Agamemnon fell silent. There was a tremendous hammering on the old oak door.

"I'll just get that," said Brother Thomond. "I think there was a knock."

As he reached it, the door burst open with extraordinary violence, sweeping old Brother Thomond aside with a crackling of many bones in assorted sizes, and throwing him backwards against the wall where he impaled the back of his head on a coathook. Though he continued to speak, the rattle of his last breath rendered the Secret unintelligible. The Mob poured in.

I ran on, into the dark of the Long Corridor.

…

I found the Master of Orphans, Brother Madrigal, in his office in the South Tower, beating an orphan in a desultory manner.

"Ah, Jude," he said. "Went the day well?"

Wishing not to burden him with the lengthy Truth, and with both time and breath in short supply, I said "Yes."

He nodded approvingly.

"May I have my Letter, Sir?" I said.

"Yes, yes, of course..." He dismissed the small orphan, who trudged off disconsolate. Brother Madrigal turned from his desk toward the Confiscation Safe, then paused by the open window. "Who are those strange men on the Lawn, waving blazing torches?"

"I do not precisely know," I said truthfully.

He frowned.

"They followed me home," I felt moved to explain.

"And who could blame them?" said Brother Madrigal. He smiled and tousled my hair, before moving again toward the Confiscation Safe, tucked into the room’s rear left corner. From the lawn far below could be heard confused cries.

Unlocking the safe, he took out the letter and turned. Behind him, outside the window, I saw flames race along the dead ivy and creepers, and vanish up into the roof timbers. "Who," he mused, looking at the envelope, "could be writing to you...?" Suddenly he started, and looked up at me. " Of course! " he said. "Jude, it is your eighteenth birthday, is it not?"

I nodded.

He sighed, the tantalising letter now held disregarded in his right hand. "Jude… I have carried a secret this long time, regarding your Birth. It is a secret known only to Brother Thomond and myself, and it has weighed heavy on us. I feel it is only right to tell you now... The secret of your birth..." He hesitated. "Is..."

My heart Clattered in its Cage at this Second Chance.

Brother Madrigal threw up his hands. "But where are my manners? Would you like a cup of tea first? And we must have music. Ah, music."

He pressed Play on the record player that sat at the left edge of the broad desk. The turntable bearing the Orphanage single began to rotate at forty-five revolutions per minute. The tone-arm lifted, swung out, and dropped onto the broad opening groove of the record, nearly dislodging from the needle a Ball of Dust the size and colour of a small mouse.

The blunt needle in its fuzzy ball of dust juddered through the scratched groove. Faintly, beneath the roar and crackle of its erratic passage, could be heard traces of an ancient tune.

Brother Madrigal returned to the safe and switched on the old kettle that sat atop it. Leaving my letter leaning against the kettle, he came back to his desk and sat behind it in his old black leather armchair.

Unfortunately, the rising roar of the old kettle and the roar and crackle of the record player disguised the rising roar and crackle of the flames in the dry timbers of the old tower roof.

Brother Madrigal patted the side of the Record Player affectionately. "The sound is so much warmer than from all these new digital dohickeys, don't you find? And of course you can tell it is a good-quality machine from the way, when the needle hops free of the surface of the record, it often falls back into the self-same groove it has just left, with neither loss nor repetition of much music. The Arm..." He tapped his nose and slowly closed one eye. "...Is True."

He dug out an Italia '90 cup and a USA '94 mug from his desk, and put a teabag in each.

"Milk?"

"No, thank you," I said. The ceiling above him had begun to bulge down in a manner alarming to me. The old leaded roof had undoubtedly begun to collapse, and I feared my second and last link to my past would be crushed along with all my hopes.

"Very wise. Milk is fattening, and thickens the phlegm," said Brother Madrigal. "But you would like your letter, no doubt. And also... the Secret of your Birth." He arose, his head almost brushing the great Bulge in the Plaster, now yellowing from the intense heat of the blazing roof above it.

"Thirty years old, that record player," said Brother Madrigal proudly, catching my glance at it. "And never had to replace the needle, or the record. It came with a wonderful record, thank God. I really must turn it over one of these days," he said, lifting the gently vibrating letter from alongside the rumbling kettle whose low tones, as it neared boiling, were lost in the bellow of flame above. "Have you any experience of turning records over, Jude?"

"No sir," I said as he returned to the desk, my letter shining white against the black of his dress. Brother Madrigal extended the letter halfway across the table. I began to reach out for it. The envelope, containing perhaps the secret of my origin, brushed against my fingertips, electric with potential.

At that moment, with a crash, in a bravura finale of crackle, the record came to an end. The lifting mechanism hauled the Tone Arm up off the vinyl, and returned it to its rest position with a sturdy click.

"Curious," said Brother Madrigal, absentmindedly taking back the letter. "It is most unusual for the Crackling to continue after the Record has stopped." He stood, and moved to the Record Player. The pop and crackle of flames was by now uncommonly loud. Tilting his head from side to side, he nodded slowly. "It is in Stereo," he said. "There are a lot of Mid-Range Frequencies. That is of course where the Human Voice is strongest... I subscribed for a time to the Hi-Fi Gazette."

Behind Brother Madrigal, the Bulge in the ceiling gave a great Lurch downward. He turned, and looked up.

"Ah! There's the problem!" he said. "A Flood! Note the bulging ceiling! The water tank must have overflowed in the attic, and the subsequent Damp is causing a Crackling in the Circuits of the Record Player. Damp” (here he touched his temple twice), “is the great Enemy of the Electrical Circuit."

He was by now required to Shout on account of the great noise of the holocaust in the roofbeams. Smoke entered the room.

"Do you smell smoke?" he enquired. I replied that I did. He nodded. "The Damp has caused a Short Circuit," he said. "Just as I suspected." He went to the corner of the room, removed a fire-ax from its glass-fronted wooden case, and strode to beneath the Bulge. "Nothing for it but to Pierce it, and relieve the pressure, or it'll have the roof down." He swung the ax up into the heart of the bulge.

A stream of liquid metal poured over him, as the pool of molten lead from the burning roof found release. Both ax and man were coated in a thick sheet of still-bright lead that swiftly thickened and set as it ran down Brother Madrigal’s upstretched arm and upturned head, encasing his torso before pooling and solidifying in a thick base about his feet on the smoking carpet.

Entirely covered, he shone under the electric light, ax aloft in his right hand, my letter smouldering and silvered in his left.

I snatched the last uncovered corner of the letter from his metallic grasp, the heat-brittled triangle snapping cleanly off at the bright leaden boundary.

In that little corner of envelope nestled a small triangle of yellowed paper.

My fingers tingled with mingled dread and anticipation as they drew the scrap from its casing. Being the burnt corner of a single sheet, folded twice to form three rectangles of equal size, the scrap comprised a larger triangle of paper folded down the middle from apex to baseline, and a smaller, uncreased triangle of paper of the size and shape of its folded brother.

I regarded the small triangle.

Blank.

I turned it over.

Blank.

I unfolded and regarded the larger triangle.

Blank.

I turned it over, and read…

gents

anal

cruise.

I tilted it obliquely to catch the light, the better to reread it.

gents

anal

cruise.

The secret of my origin was not entirely clear from this fragment, and the tower was beginning to collapse around me. I sighed, for I could not help but feel a certain disappointment in how my birthday had turned out.

I left Brother Madrigal's office. Behind me, the floorboards gave way beneath his lead encased mass. I looked back, to see him vanish down through successive floors of the tower.

I ran down the stairs. A breeze cooled my face as the fires above me sucked air up the stairwell. Chaos was by now general and Orphans and Brothers sprang from every door, laughing, and speculating that Brother McGee must have once again lost control of his Woodwork Class.

The first members of the Mob began to push their way up the first flight of stairs, and, Our Lads not recognising the newcomers, fisticuffs ensued. I hesitated on the first-floor landing.

One member of the Mob broke free of the mêlée and, seeing me, exclaimed "There he is, boys!" He threw his Hat at me, and made a leap in my direction. I leapt sideways, through the nearest door, and entered Nurse's quarters.

Nurse, the most attractive woman in the Orphanage, and on whom we all had a crush, was absent, at her grandson's wedding in Borris-in-Ossary. I felt it prudent to disguise myself from the mob, and slipped into a charming blue gingham dress. Only briefly paralysed by pleasure at the scent of Nurse’s perfume, I soon made my way back out through the battle, as Orphans and Farmers knocked lumps out of each other.

"Foreigners!" shouted the Farmers at the Orphans.

"Foreigners!" shouted the Orphans back, for some of the Farmers were from as far away as Cloughjordan, Ballylusky, Toomevara, Ardcrony, Lofty Bog, and even far-off South Tipperary itself, as could be told by the unusual sophistication of the stitching on the leather patches at the elbows of their tweed jackets and the richer, darker tones, redolent of the lush grasslands of the Suir valley, of the cowshit on their Wellington Boots.

"Dirty Foreign Bastards!"

"Fuck off back to Orphania!"

"Ardcrony Ballocks!"

The sophisticated farmer, who had seen The Radio Head at Punchestown, was hurled over the balcony, and his unconscious body looted of its shop-bought cigarettes by the Baby Infants.

I appeared, in Nurse’s attire. The crowd parted to let me through, the Young Farmers removing their Hats as I passed. Some Orphans shouted "It is Jude in a Dress!" but the unfortunate sexual ambiguity of my name served me well on this occasion and allayed the suspicions of the more doubtful farmers, who took me for an ill-favoured girl who usually wore Slacks.

At the bottom of the stairs, I found myself once again in the deserted Long Corridor.

From behind me came the confused sounds of the Mob in fierce combat with the Orphans and the Brothers Of Jesus Christ Almighty. From above me came the crack of expanding brick, a crackle of burning timber, sharp explosions of window-panes in the blazing tower.

The Mob would not rest till they found me.

My actions had led to the destruction of the Orphanage.

I had brought bitter disgrace to my family, whoever they should turn out to be.

I realised with a jolt that I would have to leave the place of my greatest happiness.

With a creak and a bang, the South Tower settled a little. Dust and smoke gushed from the ragged hole in the ceiling through which the lead-encased body of Brother Madrigal had earlier plunged. I gazed upon him, standing proudly erect on his thick metal base, holding his axe aloft, the whole of him shining like a freshly washed baked bean tin in the light of the setting sun that shone in through the open front door at the end of the corridor,.

And by the front door, hanging from the coathook in his skull, his posture more alert than his old bones had been able to manage in life, was Brother Thomond. The bright yellow straw that burst up out of the neckhole of his cassock and jutted forth from his black sleeves was stained dark red by his old, slow blood on its slow voyage to the floor.

And in the doorway itself, hung by his neck from a rope, was my old friend Agamemnon, his thick head of long golden hair fluffed up into a huge ruff by the noose, his mighty claws unsheathed, his tawny fur bristling as his dead tongue rolled from between his black lips to eclipse his fierce, yellow teeth.

What was left for me here, now?

With a splintering crash, a dull movement of air through a long moment of near-silence, and a flat, rumbling, bursting impact, the entire facade of the South Tower detached itself, unpeeled, and fell in a long roll across the lawn and down the driveway, scattering warm bricks the length of the drive.

Dislodged by the lurch of the tower, the Orphanage Record Player fell, tumbling, three stories, through the holes made by Brother Madrigal himself, and landed rightway up by his side with a smashing of innards.

The tone arm lurched onto the Record and, with a twang of elastic, the turntable began to rotate. Music sweet and pure filled the air and a sweet voice sang words I had only ever heard dimly.

"Some...

Where...

Oh…

Werther…

Aon…

Bó... "

I filled to brimming with an ineffable emotion. I felt a great... presence? No, it was an absence, an absence of? Of... I could not name it. I wished I had someone to say goodbye to, to say goodbye to me.

It is a sad song, I think.

The record ground to a slow halt with a crunching of broken gear-teeth. I felt a soft touch on my cheek, then on the back of my hand.

I looked down to see the great ball of Dust, dislodged from the Record Player's needle during the long fall, drifting the last few inches to the ground.

I looked around me for the last time and sighed.

"There is no place like home," I said quietly to nobody, and walked out the door onto the warm bricks in my blue dress. The heat came up through the soles of my shoes, so that I skipped nimbly along the warm yellow bricks, till they ended.

I looked back once, to see the broken wall, the burning roof and tower.

And Agamemnon dead.

END

Jude's continuing adventures, on Amazon...

Jude's continuing adventures, on Amazon...