Extreme Metaphors: Selected Interviews with J.G. Ballard, 1967-2008

/To celebrate the paperback release this week of Extreme Metaphors: Selected Interviews with J.G. Ballard, 1967-2008, I've reprinted my Irish Times review of the 2012 hardback, below. (That original review has now vanished into the Irish Times archive, behind the paywall.) For those too busy to read the whole review: basically,Extreme Metaphors was my book of the year. I read it with delight, frequently chortling. An extraordinary alternate history of the 20th century, packed with prescient ideas which help explain the 21st.

- Julian

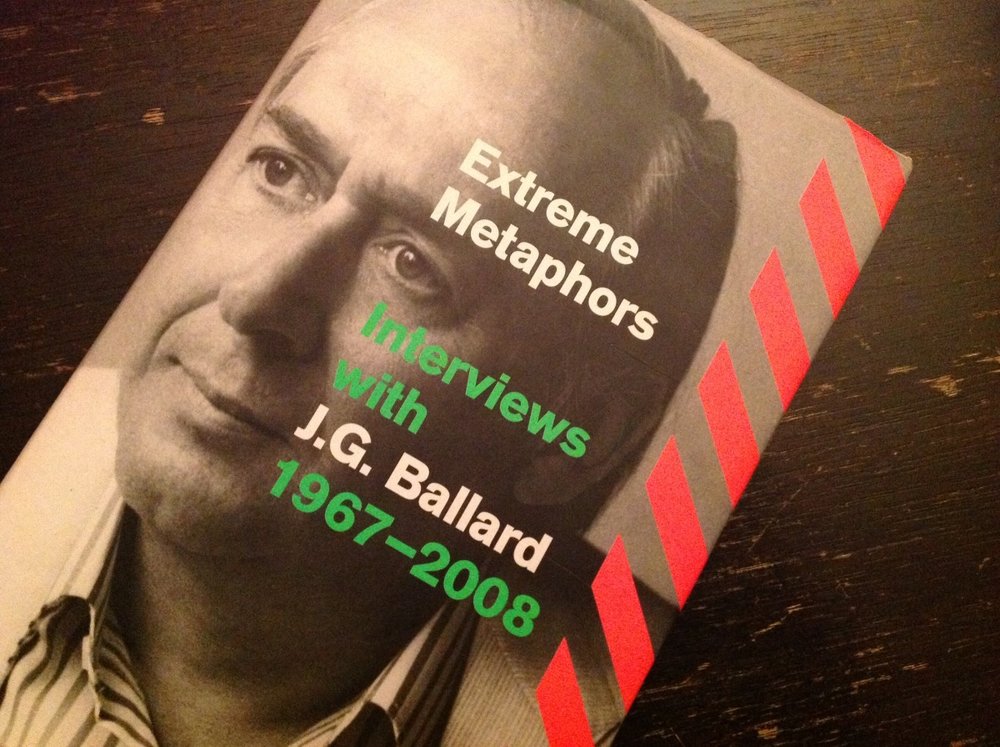

A photo of my copy of Extreme Metaphors, taken five minutes ago. The image links to more information, from the website of one of the editors, Simon Sellars.

A photo of my copy of Extreme Metaphors, taken five minutes ago. The image links to more information, from the website of one of the editors, Simon Sellars.

Extreme Metaphors: Selected Interviews with J.G. Ballard, 1967-2008

Edited by Simon Sellars and Dan O’Hara

Fourth Estate

503pp, price £stg25

J.G. Ballard might be the greatest English writer of the 20th century. He was certainly, for much of the second half of that century, the least understood, and most misread, when he was read at all. In 1970, when Nelson Doubleday Jr, a senior executive at Ballard’s American publishing house, finally got round to reading a finished copy of The Atrocity Exhibition, he was so horrified he ordered all copies pulped. In the UK, the reader’s report for Ballard’s 1972 novel Crash famously said “This writer is beyond psychiatric help. Do not publish.”

But live long enough, and respectability eventually covers you, like jungle vegetation claiming a wartime runway. In 1984, his most nakedly autobiographical novel, Empire of the Sun, was shortlisted for the Booker Prize. Martin Amis says on the back of this handsome hardback collection of interviews, “Ballard will be remembered as the most original English writer of the last century.” Will Self concurs; “Ballard issued a series of bulletins on the modern world of almost unerring prescience. Other writers describe; Ballard anticipated.”

Ballard most certainly did. The chapter of The Atrocity Exhibition which so disgusted Ballard's own publisher was titled “Why I Want To Fuck Ronald Reagan”. In it, Ballard portrayed the former Hollywood actor, who’d co-starred with a chimpanzee in Bedtime for Bonzo, as President of the United States. It would be over a decade before reality caught up with Ballard’s imagination.

Indeed, some of the interviews here are almost comically prescient; Ballard predicted Facebook before the internet even existed. In 1979, dismissing the BBC and ITV news as “that irrelevant mixture of information about a largely fictional external world”, he describes a future in which we video everything, and

“…the real news of course will be a computer-selected and computer-edited version of the day’s rushes. ‘My God, there’s Jenny having her first ice cream!’ or ‘There’s Candy coming home from school with her new friend.’ Now all that may seem madly mundane, but, as I said, it will be the real news of the day, and how it affects every individual.” (And yes, he goes on to predict Youporn…)

He predicts the future; but he also questions the present. And many of the questions he raises here have not yet been answered. The real issue, behind all the fake issues, in this year's American election [2012], was summed up succinctly by Ballard in 1984, talking to Thomas Frick:

“Marxism is a social philosophy for the poor, and what we need badly is a social philosophy for the rich.”

As with a number of the more interesting American SF writers of his era (Philip K. Dick, Thomas M. Disch, John Sladek), Ballard became a science fiction writer by default. The SF market was the only available outlet for fiction this odd. But he is not a science fiction writer. He is not, indeed, a writer, in the normal sense of the term. Ballard is a visual artist. He makes the point again and again here; the greatest influences on his works are not other literary works; they are the paintings of the surrealists. As he said in an interview with James Goddard and David Pringle in 1975,“They’re all paintings, really, my novels and stories.”

And it is true. You read his spare, functional prose, and the most astonishing images erect themselves in your mind. The beauty of the sentence itself didn’t interest him. (This makes him hard to quote: reading Ballard, you drift into a dreamstate which can’t be evoked in a couple of lines.) Certainly he set much of his work in the future. But there isn't a space ship to be found. (Well, OK, one, in an early story.) As mainstream SF explored outer space, J.G. Ballard explored what he came to call inner space. He wasn't similar to SF writers like Heinlein and Asimov and Arthur C. Clark, he was their opposite, a point he makes in an interview from 1975:

“You can’t have a Space Age until you’ve got a lot of people in space. This is where I disagree, and I’ve often argued the point when I’ve met him, with Arthur C. Clarke. He believes that the future of fiction is in space, that this is the only subject. But I’m certain you can’t have a serious fiction based on experience from which the vast body of readers and writers is excluded.”

I get the feeling J.G. Ballard passed Ireland by. He was seldom piled high on the front tables in Easons. Seen, perhaps, as too English for our tastes? But of course, he wasn’t English at all. His sensibility was formed in Shanghai, where he was born to English parents in 1930; and in particular in the vast civilian internment camp of Lunghua, where he was interned by the Japanese (at the age of 11), along with his family. In this book he frequently talks of never getting used to the England he first encountered aged 16, in 1946, as a traumatised child of the tropics.

Exiled from Shanghai, an alien in England, Ballard nonetheless had a spiritual home. No matter where his books were ostensibly set, Ballard always wrote about America; not as a place, but as a state of mind. America as a condition. America as a psychological disorder… He loved America. Though Crash is set in England, on the motorways connecting his quiet home in Shepperton to London, the cars in Crash are American cars. His Shanghai childhood — in an Americanized Asia — was a century ahead of its time. He grew up in the future. As a result, these interviews have aged well. It helps that Simon Sellars and Dan O’Hara have edited this 500 page book with such love, intelligence, and deep knowledge of the material and its context. Extreme Metaphors presents, in chronological order, 44 interviews from the many hundreds he gave. (The editors estimate the total wordage of the novels as 1,100,000; short stories, 500,000 words; non-fiction, 300,000… and interviews, 650,000.) The interviews they’ve chosen have a very low fluff content. Many of the best originally appeared in long-vanished, never-digitised, photocopied fanzines, and are genuine, deeply engaged and engaging conversations about important subjects. Nobody is trying to sell you anything (it’s often impossible to tell what book Ballard is supposed to be promoting).

The wide range of interviewers adds to the pleasure of the book. Ballard attracted intense, usually male, interviewers, who had a deep engagement with his work. There is a pleasantly kaleidoscopic effect, as each sees Ballard through the lens of their obsession. Fellow novelists Toby Litt, Will Self and Hari Kunzru take a literary approach. John Gray is philosophical. The Russian Zinovy Zinik gets Ballard to talk about Soviet utopias and dystopias. With Iain Sinclair, Ballard discusses the design of 1970s multi-story carparks in Watford. (Ballard; “They covered them in strange trellises. It was a bizarre time.”)

And he is very open. When Joan Bakewell says of Crash, “Now, this is a deeply disturbing book. Were you very disturbed when you wrote it?” he replies “I think I was. I think in a way the novel is the record of a sort of mental crash that I had in the mid-sixties after the death of my wife…”

Ah, death. Yes, it’s everywhere in his work. Ballard’s fiction is largely set in the dead spaces of the modern world. Underpasses, flyovers; abandoned and disintegrating runways; nuclear test sites; blockhouses; drained swimmingpools. The tide of humanity has gone out. What is left is returning to the natural world. The atmosphere is that of Max Ernst’s Europe After The Rain. The organic and the inorganic are inextricably linked. Things grow, and things crumble. The work of man is absorbed by the jungle.

It’s hard, reading this book, not to think of contemporary, Americanised Ireland, with its motorways and drive-thru McDonalds. Of Dublin, with its low corporate tax rate, reckless financial zone, and Euro-HQs of American corporations; with its expat communities of British, German and US workers in gated dockside settlements, surrounded by grinding native poverty; an open city, in a state too weak to defend itself. Dublin was, for a decade there, the closest thing Europe had to the booming, buckaneering Shanghai of the 1930s.

Now, in neglected Dublin back gardens, the outdoor hot tubs fill with dead leaves. Beyond the M50, the ghost estates are reclaimed by the whitethorn bushes. Ireland has become a Ballardian landscape. Given the extraordinary relevance of his work to Ireland’s psychological condition, it might be time for more Irish people to start reading J.G. Ballard. And this lovingly curated book of interviews is a fine place to start.

I will be very surprised if any novel this year gives me as much pleasure as this book. And I can guarantee (now that Ballard is dead) that no novel will contain so many provocative, intriguing, and visionary ideas.

Julian Gough is an Irish writer, living in Berlin, whose work was shortlisted this year for both the Bollinger Everyman Wodehouse Prize and the BBC International Short Story Award. His latest novel, Jude in London, is out now in paperback from Old Street Publishing.

ENDS.