Mapping Economics Onto Reality

/

Did I mention I'm reading in Prague next week? Oh, I'll blog about that tomorrow.

I spent today arguing about MFA programs, over on the New York Times' Papercuts blog. You can tell I'm dodging some serious writing, huh? A typical contribution from me went something like this...

"Literature is, among other things, a long cascade of mentorings. Fitzgerald helped Hemingway. Beckett sat at the foot of blind Joyce, taking dictation for Finnegans Wake.

But Fitzgerald didn’t invoice Hemingway. And Beckett didn’t have to pay Joyce $100,000 to sit there.

(In fact, Joyce paid Beckett - in cast-off clothes, neither of them being commercially glorious).

It is remarkably cheeky of the universities to try to put mentoring - something which has to be extraordinarily personal, intimate, and freely given, if it is to have any meaning - on a sound commercial footing. Buying the mentoring of better writers is an extraordinary form of prostitution, which degrades both parties. (You should hear what creative writing teachers say to each other about their students after a workshop. Very reminiscent of what prostitutes say to each other after the johns have left.)

Perhaps, occasionally, a good writer will discover a potentially good writer, and real mentoring will take place. But what is the moral condition of the vast mass of relationships which have been forced into existence? Bad faith, bad faith.

And there is a more fundamental philosophical problem.

The novel is against authority, or it is nothing.

The university is authority, or it is nothing.

The two are uniquely unsuited to a close embrace.

Universities (given the way society is currently organised), have to expand. Sometimes they expand into territory to which they are wildly unsuited. The novel is one place they should never have ventured. Claiming to “teach” creative writing for money is morally dubious. But for the universities to employ such large numbers of potentially good writers as teachers, forcing them to daily read the worst prose ever written… well, it’s the kind of hellish torture Dante would have found a bit much. What sin could have earned such punishment?

Betraying your muse, perhaps.

The MFA in creative writing is a very successful industry. But its main product is embittered teachers of creative writing, (who nightly stifle the thought of what they might have written had they not had to read, grade and workshop student dreck for 20 years).

Not writers."

I, of course, totally overstate my case, and repeatedly break my only rule, that a writer should have no opinions.

The whole thing, may God have mercy on us all, is here.

I just wrote a long, complicated, fairly well-researched post about the collapse of Bear Stearns. When I went to save the post, it, for annoying technical reasons, vanished. Forever.

(I can hear you cheering from here.)

Obviously, the loss of a big, long economics post is good news for YOU, but I am unhappy.

I am going to bed now.

"A financial sector that generates vast rewards for insiders and repeated crises for hundreds of millions of innocent bystanders is, I would argue, politically unacceptable in the long run."

And that's Martin Wolf, associate editor and chief economics commentator at the Financial Times (and author of the very fine Why Globalization Works), writing today. God knows what the Socialist Workers' Party is saying.

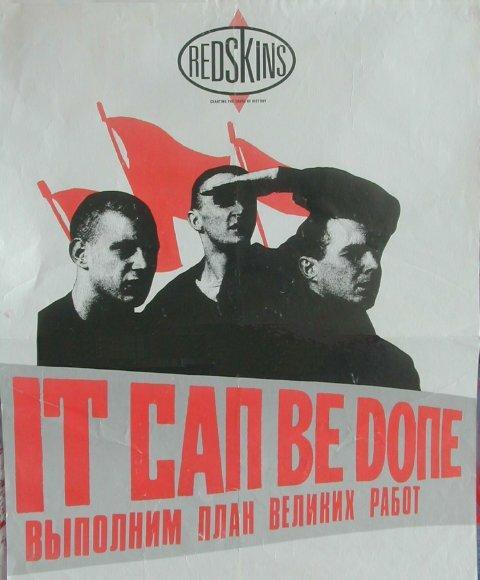

Oh, wait, they're saying this:

"The sophistication of the financial system had encouraged the major banks to engage in increasingly speculative activities. (...) So a crisis developing in the financial system has the potential not only to hit capitalists’ investments – it can hit workers’ consumption."

(The entire SWP analysis of the financial crisis is here.)

(The entire FT analysis is here.)

It's a measure of the almost comical enormity of the financial sector screw-up that the banks have managed to provoke the Financial Times and the Socialist Workers' Party into writing practically the same article attacking them.

This is truly the World Cup Final of international financial meltdowns! America, staring defeat in the face, brings on super-sub Ben Bernanke, Chairman of the Federal Reserve! He's on the pitch! He's scored a hattrick! Can he win the game???

Well, the US Federal Reserve panicked. Ben Bernanke cut interest rates by .75% an hour before the US markets opened.

Yes, to change metaphors, Ben wields the mightiest hammer in the world, and he has just struck the problem a decisive blow.

Trouble is, the problem is not a nail. No, it won't work. Markets will be heading south again within the week. He can only cut a few more times. Markets that need to fall can fall every day God made.

To change metaphor yet again (you can tell I'm a novelist, huh?), US markets have been permanently drunk for nearly two decades. Every time they were in danger of sobering up, the Fed poured more liquidity down their throats, to save them from a savage hangover.

That just put off the hangover, and ensured it would be worse when it came. Ben is pouring alcohol down the throat of a strong man who has finally passed out from alcohol poisoning.

... and the Asian markets continue to fall. India's stock exchange fell 11% in the first minute of trade this morning (Tuesday, January 22nd, 2008). Trade was automatically suspended for an hour before reopening. (If it falls 15%, there will be another automatic suspension).

So what will happen in the US when markets open? Well it's kinda hard to see them going UP. But on a day this volatile, there will be wild swings, as automatic trading algorithms are triggered to pump out enormous buy and sell orders (remember, some traders are making a ton of money by shorting this market... it falls, they win). So, wildly up and down, but mostly down. A serious opening plunge.

Should be a shambles. I'm guessing US markets will also be automatically suspended for a time today.

Well, Fitch did their best. They gave the US markets three days to come up with a plan. (They downgraded Ambac after the markets closed on Friday, just before the long US holiday weekend for Martin Luther King's birthday.) But what plan can you come up with? There's going to be a lot of forced selling into a falling market.

And there's no fixing the fundamental problem: a lot of the "wealth" created in the past few years, from insanely high house prices to comically complicated and poisonous derivatives rated a perfect AAA, was fairy gold, destined to fade away as we awoke from the dream of unlimited wealth for doing nothing at all.

Wow, that was quick. Very gratifying.

On Friday, I predicted a massive multi-market meltdown as a direct result of the downgrading of the monolines. (Or, as I poetically put it, "if you ARE into economic meltdowns, this is going to be the World Cup Final of economic meltdowns, and Brazil are about to walk out onto the pitch...") On the next trading day (today, Monday), markets collapsed all over the world.

Or as the New York Times put it, with their usual blissful ignorance of what actually drives markets,

"Fears that the United States is in a recession reverberated around the world on Monday, sending stock markets from Bombay to Frankfurt into a tailspin and puncturing the hopes of many investors that Europe and Asia will be able to sidestep an American downturn. "

Isn't that beautiful? All the world's stock markets except the ones in the USA keel over (US markets are closed for Martin Luther King's birthday), and the New York Times report starts with the words "Fears that the United States..." and end with the words "...an American downturn." Everything has to be about them. Sigh...

Well, they captured about 40% of the truth (about the NYT average for any story that isn't about baseball or a quaint, family-owned deli that's celebrating its fiftieth anniversary by going out of business). Today's market collapses are, in certain respects, about the coming US recession. But they're more about the fact that on Friday, a ratings agency (Fitch) downgraded a monoline insurance company (Ambac) from AAA to AA, and put them on watch for further downgrades. For why that blew everything out of the water, see my previous post.

Why would that shake world markets enough to cause an avalanche of panic? Because there's only roughly half-a-dozen decent-sized monolines, and between them they insure between three and four trillion dollars worth of bonds. Call it three and a half. That's $3,500,000,000,000. Count the zeroes... Ambac was the oldest monoline (born 1971) and the second biggest, and downgrading it automatically meant downgrading over 100,000 different bond issues, with a total value of roughly half a trillion dollars (or five hundred billion, if you're into mere billions.) Bonds issued to build libraries in Stuttgart, or a bridge in Seattle. Bonds issued to fund corporate buyouts in Tokyo. And, recently, bonds stuffed with dodgy mortgages from who knows where... Bonds owned by everyone from investment banks to your dad's pension fund.

Ambac's slogan? "Financial peace of mind". And what prestigious award did it win one month ago? Global Monoline of the Year. Ah, I love the modern world, but it makes life hard for satirists.

Let's have a quote from a respected market insider, so you don't think I'm exaggerating the carnage(God forbid). This is John Authers, the unflappable, seen-it-all Investment Editor of the splendid Financial Times:

"On days like Monday, there is little to do but wait for the casualty count at the end. Even with the US on holiday, the sell-off was the worst single day for global equity markets since the terrorist attacks of September 11 2001."

The Financial Times' coverage of this ongoing credit debacle has been superb, before and during. Sigh. It's so superior to the Wall Street Journal that the continued existence of the Wall Street Journal seems to me evidence that there is no God. Or that he just doesn't care.

And the US markets open again tomorrow... That'll be interesting...

OK, my next prediction (these are going rather well): the collapse of the Chinese stock market, leading to widespread protests and social unrest in China. Timescale... Hmmm. Let me be conservative (I tend to be hasty and assume if something is obvious, it will happen right away). Well, over the next year and a half, almost definitely. But probably a lot (a LOT) sooner.

Much more than cut in half from its peak. Could go down to a third or even lower. There you go. More hostages to fortune...

Of course, a totalitarian state has powers of intervention undreamt of in the West, so it'll be interesting to see what the Chinese government will do in response to serious falls (which could well have begun, it's already slipped from its peak).

What larks!

Look, I've got to talk about what's happening in the financial markets or I'll burst. Feel free to ignore it, I know almost none of you care, but I'm incredibly excited. And if you ARE into economic meltdowns, this is going to be the World Cup Final of economic meltdowns, and Brazil are about to walk out onto the pitch...

Well, anyway, for the few of you still reading... You might remember, I made a big, fat general prediction back in February 2007. I said, in this blog:

"At some point in the next five years (but my gut feeling is much sooner, within the next two years) there will be almost simultaneous collapses in the valuations of many unrelated asset classes across much of the world."

I also said:

"By definition, an unexpected collapse will be unexpected. It's impossible to predict the trigger, and foolish to predict the timing. But if it pops, the feedback loop which pumped it up will reverse and act to deflate it. There will be a horrible drying up of liquidity, a credit crunch, and a fairly general asset crash."

Bear in mind, this was six months before August 2007, when the current credit crisis started.

I also said, (as I outlined the historical process that leads to these things):

"Step one: A great idea. You can hedge risk by buying a derivative: for example, if you own General Motors bonds, you can insure against the risk that General Motors will go bust by buying a credit default derivative for those bonds. The derivative will pay out if General Motors goes bust. Voila! You now have no risk. Ultimately, either the bonds will pay up, or the derivative will pay up."

That was the theory for the past insane decade, and a very sweet and charming theory it was. But it was bullshit, and here's why...

Somebody has to be on the other end of that bet. Someone has to sell you that credit default derivative (let's call it an insurance policy). And if the bond does default, if General Motors does go bust... That someone who sold you the insurance has to have the money to pay you. And if that someone has mispriced the risk... has sold everybody around the world cheap, cheap, cheap insurance, firmly believing the policies will never have to pay up... And suddenly has to pay up... The money isn't there. The premiums were not enough to cover the risk.

The ultra-cheap insurance made everybody (banks, companies, hedge funds, private equity firms, individual investors, your mamma) happy to take on too much risk. Taking on too much risk, they eventually collapse. Collapsing, they trigger the insurance. Which bankrupts the insurance companies.

Which wipes out everyone's insurance, which causes banks, companies, everybody, to default, collapse, implode, as they get downgraded by the ratings agencies, and investors run like rabbits for the hills.

Well it's happening, right now. There are only a few big companies who insure all the bonds issued by everyone from IBM to your local town council. They are called monolines. And, in my opinion, they have been technically insolvent (or broke, as we used to call it) for months. But the ratings agencies haven't had the guts to downgrade the monolines' ratings, for fear of the consequences. This cannot last forever: the monolines ARE broke, and they WILL go bust (unless some generous soul from outside intervenes and bails them out), and the ratings agencies cannot pretend they're OK indefinitely...

Ah, enough for tonight. (It's not like anyone reads my economics stuff anyhow.)

Recycling is boring. It turns people off. If the future of the planet depends on recycling, we're screwed. It might be good for the climate, but it's anticlimactic. You go to all the trouble of carefully sorting your rubbish into categories - a lid here, an eggshell there - and what do you get for your trouble and pain? Depressed men grab your bin, haul it to a lorry, and tip it in. They don't even look at your rubbish! And you spent all that time arranging the orange peels, coffee grounds and old tagliatelle to look like a Jeff Koons oil painting! It's a slap in the face.

No. Recycling needs glamour. It needs danger. You need some sort of immediate reward, a payoff, for bothering. What it needs is something like, oh I don't know, wild animals, say, tearing apart your rubbish, and eating it before your very eyes.

Well, Germany has been leading this exciting new field for quite a few years now. Here in Berlin, you leave out your old Christmas trees on specific days in January for collection, and the Berlin council workers bring the trees to the Zoo, and feed them to the elephants.

As Ragnar Kuehne of Zoo Berlin told Reuters last January,"Elephants around the country will enjoy a delicious lunch today consisting of about five Christmas trees each."

Apparently, pine resin is good for their digestion. The camels and deer also get to join in the January feast. It's been a huge success, with public and animals alike. Indeed, there are rumours that soon, for a little extra, they will bring a baby elephant to your house, where it will eat your Christmas tree, live, in front of your cheering children.

Once the private sector gets involved, there'll be no stopping it. Across Prenzlauer Berg, wild, proud mountain goats will leap from bin-top to bin-top, pausing only to eat your old cardboard and newspapers. Already, in certain high-class restaurants here in Mitte, hyenas are being trained to lick your plate clean after the meal.

This is the future of recycling.

I love Berlin.

None of my friends want to talk to me about economics, which is frustrating. Because I think we are in for an almighty wipeout in the financial markets, which has only barely begun to get going. And that is interesting, and worth a conversation.

As I have posted previously, I think a lot of exotic financial products, and a lot of very exotic investment strategies done with borrowed money, are about to fail spectacularly. As a side effect, a lot of perfectly solid markets (in stocks, bonds, property, commodities) are going to be cut in half, and a lot of institutions, to their intense surprise, are going to be wiped out.

More specifically, I predict the implosion of a very large number of hedge funds over the next year or two (and probably a lot sooner than that). Let's be more specific: I suspect that more than 25% of the hedge funds in existence today will not exist in two years time. (Oh come Julian, don't be shy, what do you REALLY think? Well, I really think at least half of them could vanish, but I'm trying to sound conservative and thoughtful here.)

And I think we'll lose more than one really, really big, globally known bank, insurer, and/or pension fund.

We may not lose them technically: governments and central banks will probably try to coordinate a rescue. But if they survive, they'll have been artificially resuscitated after having gone under.

Also, a lot of junk bonds will turn out to be junk. A shedload of private equity firms will go bust, and a stack of grossly overleveraged companies will collapse before 2010.

And residential property prices will fall through the floor in real terms over the next couple of years in a bunch of countries, including the USA and my dear and darling Ireland. (Put a figure on it... OK, from peak to trough, a fall of over 30 % in real terms. There. The trough may well take a lot more than a couple of years, mind you, and inflation may mask the fall, but in real terms I'd be surprised if it's less than 30% in Ireland's case. America, being vast and varied, I'll call a fall of over 30% on the coasts and large urban areas, before it eventually bottoms out. Again, I'm being conservative, and secretly think it could be more.)

Note that I think the real-world economy is in pretty good nick right now. But the financial world, across many asset classes, is about to have the biggest crash (in dollar terms) in the world's history. Bigger than the dotcom blowout? Yes. Will it wreck the real economy? Don't know. Haven't I predicted enough for ye? Don't be greedy.

Ah, sure, while we're at it, we'll lose at least one of the Big Three American car companies.

Well, that has the potential to make me look very stupid indeed in 2010...

Anyone want to argue?

Warning: This is solid economics all the way to the end, and it's long. So, please, skip it if this kind of thing doesn't interest you. I will totally understand.

Sigh. OK. For the last week, I've been meaning to predict a global economic disaster, but never got round to it. And now there's this big 9% Chinese stock market fall today, which has jolted the US markets down 3%, so if I post now I'll look like Chicken Little, hit by an acorn and screaming "The sky is falling! The sky is falling!"

But, sheesh, I'll do it anyway. Here's my prediction, based a little on economics and a lot on history and human nature. At some point in the next five years (but my gut feeling is much sooner, within the next two years) there will be almost simultaneous collapses in the valuations of many unrelated asset classes across much of the world.

OK, why? Because almost every major unregulated financial innovation starts out being used for its intended purpose, gets misused by more and more mainstream financial institutions to make free money, and is pushed to grotesque excess, leading to the unexpected collapse and disgrace of often venerable institutions, followed by reform and regulation.

The new derivatives (especially some of the credit default ones, and some of the very, very weird and complex derivatives-of-derivatives) are classic examples of this.

Step one: A great idea. You can hedge risk by buying a derivative: for example, if you own General Motors bonds, you can insure against the risk that General Motors will go bust by buying a credit default derivative for those bonds. The derivative will pay out if General Motors goes bust. Voila! You now have no risk. Ultimately, either the bonds will pay up, or the derivative will pay up. Banks also get excited, because they can shift risk off their books by packaging debt (say a bundle of mortgages) and selling it as a product. Risks can be spread more widely. This should lead to greater stability in the markets, and safer banks. And it would, if human nature didn't lead inevitably to...

Step two: Misuse. People and institutions start to get really, really interested in the derivatives themselves, and not the underlying asset, as the derivatives themselves become tradable assets. At first it's just people buying and selling derivatives they don't need. Someone with no General Motors bonds buys a credit default derivative for those bonds, because he figures it's better value than the bonds. Now debt, and risk, start to change meaning: Instead of being locked in place between a lender and a borrower, debt and the debt's risk can be moved, separated, repriced, sold, resold, shuffled, combined with something else, repackaged, renamed, rebranded, remarketed, in derivatives of derivatives of the original thing, whatever the hell that was.

Step three: Grotesque excess. The relationship between derivatives and the underlying assets becomes totally meaningless. The value of outstanding derivative contracts becomes massively greater than the value of all the assets on earth. Many derivatives are now pure and simple speculation (or "bets" as they used to be known.) But there is a feedback mechanism now exaggerating the situation and pushing it to its limit (and crisis). The removal of risk from the lending institutions leads to far more lending than would otherwise be the case. The removal of risk from the borrower means that companies and institutions are far more keen to borrow than they would otherwise be. Much of the lending and borrowing is to buy unanchored assets which only exist because of the extraordinary liquidity of the financial markets. Real-world debt is now an asset in high demand: therefore, there is immense pressure to supply it.

An example: Banks which once made their money slowly, from mortgage borrowers slowly paying back their mortgages, now make much more money, much faster, by slicing-and-dicing the mortgage debt into complex derivative products and selling it to hedge funds. So the bank's primary customer becomes the hedge fund, not the guy buying a house. The product the bank is selling has changed: it's no longer selling money to people who need money: it's selling debt, to institutions that need to buy debt. And almost any mortgage to almost any individual becomes profitable, because the supply of real world debt is the only bottleneck, in a world awash with liquidity.

Step four: Unexpected collapse. The global house price bubble is largely explained by this hunger for real debt to repackage. A lot of other assets are now at silly prices because the illusion of no risk has led to vast over-lending into a limited pool of real-world assets. The consequent pumping up of real-world asset prices keeps the whole game going. But risk hasn't been eliminated: it's merely been moved around (and, I believe, mispriced).

There is also, in total, a lot more of it than there was before. A crash has become less likely, on a day-to-day basis; but it will be larger and spread across more territory and asset classes when it does.

By definition, an unexpected collapse will be unexpected. It's impossible to predict the trigger, and foolish to predict the timing. But if it pops, the feedback loop which pumped it up will reverse and act to deflate it. There will be a horrible drying up of liquidity, a credit crunch, and a fairly general asset crash.

But, to end on an up note, the underlying real-world economy is in fact in excellent nick (on its own terms, but that's a different debate). It is also, now, a system of such tremendous complexity that it is in fact quite stable. (The mathematics of large complex systems are very interesting and often counterintuitive). It will bounce back surprisingly quickly. And once derivatives and hedge funds are properly regulated, they will indeed bring greater stability to the financial system. Until the next major innovation.

OK, that's it. Glad I got it off my chest. And don't worry, it's just my pet theory. I could also be quite wrong. Nobody really knows what the hell is going on in the financial markets these days. They're now just too vast and complex to model. And they involve the one factor that can totally screw up any prediction: lots and lots and lots of people, living their lives, and making their decisions, and reacting to events while creating new events in a real world that exists on a plane that transcends any theory.

If you made it all the way to the end of that, my God, you're a hero. Thanks for sticking with it. Buy yourself a cup of coffee. Have a biscuit too, you deserve one.

The website of Julian Gough, author of Connect, Juno & Juliet, the Jude novels, and the ending to Minecraft. He is also the author of the Rabbit & Bear children’s books (illustrated beautifully by Jim Field).

This sidebar rather cunningly links you to the official Substack newsletter for The Egg And The Rock. That is where I am writing my next book, in public. Which is both terrifying and exhilarating… What’s it called? Er, The Egg and the Rock. It is a beautiful book about our beautiful universe. Go and subscribe, if you want to be kept up to date as the book develops. Or if you would like to help me develop it: I love to get your comments over there. It’s free, and once you’ve subscribed, you will be emailed each new piece of the book as I write it. There is also some other fun stuff going on. Click now! Subscribe! You will not regret it! (Well, you might regret it, but then you can just unsubscribe.)

Powered by Squarespace.